The union’s least-populous member nation has become a cryptocurrency and online gambling hub plagued by allegations of corruption and money laundering. And it’s selling passports.

Good Friday claims a sacred spot on the Maltese calendar, and this year the holiday was casting its reliable spell. In the late afternoon, hundreds of people streamed from Baroque cathedrals outside the capital city of Valletta, forming slow parades through steep and narrow streets. Men in biblical robes lugged crosses, children clutched bright flowers, and small brass bands marched behind with raised trumpets and inflated cheeks. A breeze wrinkled the Mediterranean, and the sun slipped to a flattering angle, encasing all that charm in amber.

At the same time, the nation’s top-rated prime-time television show was wrapping up a special daytime broadcast: an annual telethon to raise money for children receiving cancer treatments abroad. In the bottom-left corner of the screen, a digital counter tallied the donations. When the number finally hit €1.26 million ($1.46 million), the studio audience began to stir, eager to applaud the fundraising record.

That’s when Prime Minister Joseph Muscat called into the telethon’s phone bank. He, too, seemed in a celebratory mood. The day before, the country had announced that it had registered a €182 million surplus for 2017, its second straight year in the black after decades of deficits. Patched through to the telethon’s host, Muscat pledged €5 million to the cancer charity on behalf of the government, nearly quadrupling the previous telethon record in an instant. The audience erupted. Some of the operators on the dais behind the stage removed their headsets and laid them on the table, as if to declare victory.

But these days in Malta, feel-good stories never seem to last. When Muscat hinted that the donated money would come from a fund fed by Malta’s Individual Investor Programme—a government initiative that sells Maltese passports to foreigners for €650,000 (less for additional family members), plus a €150,000 investment in government bonds—Good Friday took a turn.

An opposition Parliament member wrote on Facebook that, as a cancer survivor, he was disgusted by the possibility that the patients’ care was being financed by money from “criminals and the corrupt.” Another suggested Malta was trying to clean its dirty money by funneling it through a good cause. “It’s [like] thinking that prostitution is OK once part of the proceeds are donated by the pimp to charity,” Jason Azzopardi, a Parliament member, complained on Facebook.

The story of how Malta got to this point—where a holiday donation to a children’s charity can spark outrage and lament—starts brightly enough. A tiny country carves a small but lucrative niche in the global economy. Money flows in, thousands of jobs are created, and the government intensifies the strategy, opening the country to more partners and funding sources. Then comes the twist: Allegations of money laundering, political skulduggery, smuggling, organized crime, and even a murder.

Multiple investigations—by local magistrates, American prosecutors, and European politicians and banking regulators—have been rattling Malta’s financial and political networks for more than a year. Some of the most powerful countries in the world have suggested that a nation of about 450,000 people might pose a serious threat to global efforts to track money laundering, enforce economic sanctions, and maintain fair transnational standards.

A 15-month inquiry into one of the most contentious of the allegations—one suggesting that Muscat’s wife was directly involved in setting up a shell company for money laundering—wrapped up in late July without uncovering evidence that would justify criminal charges. “One hundred threads of suspicion don’t stitch together a single strand of proof,” the investigating magistrate concluded.

The story isn’t over yet, because some of those threads still dangle, and critics of the government both inside and outside Malta remain convinced that they tie into other scandals, other crimes. The government continues to try to nurse its battered reputation back to health, and how it all turns out will likely depend on how the Maltese ultimately answer the question lingering over their country: To supercharge its financial-services sector, did the smallest country in the European Union sell its soul?

South of Sicily, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya, Malta’s three tiny islands have been eyed as well-placed steppingstones by the Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, French, and British. All coveted Malta as a staging ground, which makes its history a swashbuckling saga of raids, sieges, bombings, and rotating occupations. When the last British military base finally left in 1979, it took with it the country’s main economic engine. Malta turned to tourism, doing its best to sell ancient ruins, fortress walls, sloping medieval streets, and sheer limestone cliffs. The country eventually discovered, as most sunbaked islands do, that while it’s possible to get by on atmospherics, it’s hard to do much more.

In the early 1990s, Malta’s two major political parties argued over whether to take a shot at EU membership—generally speaking, the Labour Party didn’t like the idea and the Nationalist Party did. By the mid-’90s, with the Nationalists in power, the country began to prepare its application to join the bloc.

To convince the rest of Europe that it could be a trusted partner, Malta began instituting a series of financial and regulatory reforms. In the process, the country was reinventing itself as a new sort of steppingstone: a transit hub not for ships or soldiers but for money, in an environment of regulatory legitimacy, transparency, and stability. Malta discovered that the residue from centuries of turmoil (an ingrained adaptability, strong links to disparate cultures, the English language) was an asset, as was the country’s size, which allowed it to nimbly sidestep bureaucratic delays and cater to rapidly evolving industries that valued good computer connections more than natural resources. The traditional downsides of island economies—the high costs of transporting supplies in and out, for one—didn’t apply to the financial-services industry.

By the time the country’s membership in the EU was formally approved in 2004, Malta had staked out its place within Europe’s economy, and the nation’s attractive tax schemes—effective rates as low as 5 percent for foreign-owned companies, vs. an average of 22 percent for other European countries—helped attract investment funds, banks, and financial-services firms from all over the world. The steady influx of new business helped the local economy avoid a significant downturn during the 2008 financial crisis. Shortly after Muscat and his Labour Party took office in 2013, effectively ending 25 years of Nationalist electoral dominance, the country instituted the controversial passport-selling scheme, which was denounced by EU officials who feared it could create a back door for shady individuals or dirty money to gain access to Europe’s financial markets. But Muscat energetically pushed the plan, traveling abroad to sell it to prospective citizens, and it quickly took off. In 2014, Malta began a three-year run as the fastest-growing economy in Europe, and Muscat and his allies described the passport program as a complete success. By the beginning of this year, the government had collected about €600 million through it.

Muscat’s opponents in the Nationalist Party, as well as some members of the Maltese press, weren’t sold. In 2016 investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia dug into the documents released in the Panama Papers leak and discovered that two of Muscat’s closest aides had established companies in Panama. She accused them of using those businesses to launder money from kickbacks she said they’d received for helping to arrange the sales of passports to Russian nationals. They denied it; a separate magisterial inquiry regarding those allegations is under way.

Later, Caruana Galizia reported that Muscat’s wife, Michelle, had established her own Panamanian shell company through the same middleman who’d set up those for Muscat’s aides—the accusation that the magistrate this summer said he’d found no proof to support. Caruana Galizia also accused Pilatus Bank, a Maltese institution founded in 2014, of handling much of the money in those alleged transactions, as well as those involving the shell companies set up by the prime minister’s aides.

Additionally, the journalist alleged that the first lady had received at least $1 million from Azerbaijan’s ruling family. Last year an international consortium of investigative journalists accused members of Azerbaijan’s ruling elite of operating a $3 billion scheme to launder money, pay off European politicians, and buy luxury goods; the reports cited “ample evidence” tying the ruling family to the schemes. Azeri President Ilham Aliyev last year labeled the accusations “totally groundless, biased and provocative.”

Caruana Galizia’s blog became the most-read news source in Malta. And even though she criticized both parties, it was a clearinghouse for critics of Muscat’s government. On any given day she might have accused a Maltese official of visiting a prostitute; or exposed an alleged local oil smuggling ring that helped Libya evade sanctions; or traced personal connections between government officials and suspected criminals; or slammed Muscat for trying to pitch Malta as a cryptocurrency capital, which she suggested would attract more corruption; or detailed alleged links between the country’s growing online gaming sector and the Italian Mafia. The list of her enemies was large and growing, and by last fall she faced 47 lawsuits—42 civil, 5 criminal—about 70 percent of them from government officials, according to her sister, Corinne Vella.

Prime Minister Muscat was one of those suing her, and he labeled her accusations as “the biggest lie in Malta’s political history.” Many in Malta seemed to believe him; in June 2017, as the allegations swirled, Muscat called for a snap election, and he was reelected with 55 percent of the popular vote.

Last October, as she drove away from her house, Caruana Galizia was killed by a car bomb. Police later arrested three men, low-level criminals, for planting and detonating the device. But no one in Malta considers the crime solved. Whoever ordered the killing remains unidentified. Some speculate that criminals involved with the Libyan smuggling ring might have targeted her, or that the Sicilian Mafia put out the hit. Many others blame the government.

Muscat and his administration loudly condemned the murder, calling it a tragedy and energetically denying any link to it. But the killing marked a turning point for Malta. The notion that corruption might have overtaken Malta’s economy now spread far beyond the confines of an opposition party, and the eyes of the world turned toward the tiny country. It has been struggling to clear its name ever since.

Everyone knows everyone in Malta. It’s an exaggeration, of course, but among the nation’s financial elite, the people who run the banks and institutions and sit on the governing boards, the notion is all but taken for granted. “There are, unofficially, some 10,000 people who work in Malta’s financial industry, and the guys in charge—there are maybe 50 or 70 of us—we know each other fairly well,” says Joseph Portelli, chairman of the Malta Stock Exchange.

In describing the financial community as small and closely knit, Portelli is defending it. He grew up in New York with his Maltese parents, and 15 years ago moved to Malta to manage his own fund, which specializes in emerging-market investments. He entered a financial-services industry that was fiercely protective of its reputation and keenly sensitive to insinuations of corruption. Now, as allegations of wrongdoing swirl, that defensive sensitivity is more acute than ever. Portelli has adopted it as naturally as any lifelong resident.

“We’re getting this blemish that we’re money launderers,” he says, “and that’s the worst irony.” There have been a few small problems, he concedes, with a handful of small banks. “You know what they all have in common?” he asks. “Not one of the principals was Maltese, they were all foreigners.” The locals, he suggests, police one another.

It’s a variation on an argument that’s been around since Plato and Aristotle. Small states tend to be less susceptible to corruption for two reasons: It’s more difficult to hide indiscretions, and higher levels of social cohesion discourage dishonesty. In the early 2000s several academic studies used data to support this theory, and some analysts suggested that globalization might be of particular benefit to small countries—freer trade and the increased mobility of labor and capital would reduce the costs of being small, they argued, while the advantages associated with less corruption could be retained.

An alternative theory is that small states will be susceptible to cronyism—all those close connections might enable, rather than discourage, financial subterfuge. More recent studies, including research conducted by the World Bank, have found that the data used in the earlier reports were incomplete, and the suggestion that smaller countries are statistically less corrupt than large ones remains unproven.

For critics of Muscat, one powerful symbol of cronyism is Ali Sadr Hasheminejad, head of Pilatus Bank, the institution allegedly in the middle of the suspicious transactions involving the Panamanian shell companies linked to government officials. Sadr is an Iranian national, but when establishing and registering the bank in Malta he used a passport he’d purchased from St. Kitts. While Sadr was enmeshed in controversy in Malta, a parallel investigation into him and his bank culminated in his arrest by U.S. authorities, who charged him this spring with setting up a network of shell companies and bank accounts to hide money being funneled from Venezuela to Iran—transactions that allegedly violated economic sanctions against Iran. Prosecutors also alleged that Sadr established Pilatus Bank using illegal funds. Sadr pleaded not guilty and has been released on bail in the U.S.; his lawyer didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Malta’s government attempted to distance itself from Sadr, but the same sort of intimate connections found throughout the financial sector have undermined those efforts. Local news outlets reported that among the 250 guests at Sadr’s 2015 wedding in Italy were Muscat, his wife, and one of the aides accused of moving money from kickbacks related to the passport program through Pilatus Bank.

The July magistrate’s report stated that some of the evidence used by Caruana Galizia and others to implicate Michelle Muscat—including Pilatus Bank documents suggesting she was the owner of the shell company at the center of the scandal—bore falsified signatures. Muscat and the lawyers for Pilatus Bank immediately presented the findings as a “certification” that the whole story had been a lie cooked up by Caruana Galizia and foreign critics, and they denounced it in terms familiar to anyone conversant with the new vocabulary of political grievance: It was “fake news,” part of a “witch hunt.” They also drove home the point that the magistrate’s report identified serious improprieties on the part of their critics.

But the family of Caruana Galizia pointed out that the identity of the owner of the Panamanian shell company is still a secret. Furthermore, the European Banking Authority just weeks before had cited “serious and systematic shortcomings” in how Maltese regulators monitored Pilatus Bank before and after Sadr’s ties to Iran were exposed. A confidential 2016 regulatory report that was leaked last year confirmed that the bank’s profitability depended on politically involved clients from Azerbaijan. And the U.S. allegations that Sadr founded Pilatus Bank with criminal proceeds remain unaffected by that magisterial report.

The result of all this is a contagion of suspicion. Many of the allegations of money laundering and other financial crimes have proved difficult to either verify or dismiss outright, but collectively they make it increasingly hard to swallow the idea that corruption is strictly a foreign import here. The country’s only independent think tank, the Today Public Policy Institute, ceased operations in April. Its stated reason for closure was bluntly condemnatory: “a sense of defeatism over the government running roughshod over standards of professionalism, transparency, and accountability.”

Muscat and those in his government generally have responded to such criticisms by going on the offensive: Instead of putting the brakes on controversial policies, they’ve stomped on the gas. Muscat this year pushed for an expansion of the passport sales program, arguing that such investments and the economic activity they spur could help Malta become one of the wealthiest countries in Europe within his lifetime. Last year alone, private wealth in Malta jumped by more than 20 percent, thanks in part to its newly minted citizens.

“Globalization is like a treadmill—you can’t say you are tired, because the second you stop, you will fall off,” Muscat said during a press conference earlier this year. “Once in the race, we must not simply be there to take part, but we are there to win.” Previously he’d outlined the types of policies that would power Malta’s sprint toward success: “some sensible, others risky, yet others which might sound, and be, outright insane.”

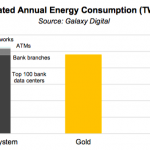

In April, just as several Asian countries were cracking down on cryptocurrencies, Muscat announced that Malta would become the first country in Europe to create a regulatory and legislative framework specifically designed to attract virtual currencies. Shortly thereafter, Binance Holdings, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, announced it was moving its headquarters from Hong Kong to Malta. Within weeks, Morgan Stanley analysts were reporting that a majority of the world’s crypto trading volume was moving through companies based in Malta.

There are people who insist that the government’s continued success in attracting investment and generating revenue is itself an answer to the disputed allegations of money laundering, kickbacks, and other financial crimes. “Luckily, this comes at a time when it washes off,” says Edward Scicluna, the country’s finance minister. “The false and fake parts are washing off, because Malta is being so successful that it’s very hard to accept them and to correlate them with a successful country. Normally corruption is rife in backward countries where there are no investments. So you find it very difficult to reconcile these two.”

In Sliema, one of the most affluent towns in Malta, open-air restaurants line the harbor road. A few decades ago, diners here would look out upon dozens of Maltese fishing boats bobbing in the water, their prows upturned and their wooden hulls painted in rainbow stripes. Now the harbor is crowded with hundreds of fiberglass yachts—large, modern, colorlessly impressive.

The view helps explain why many Maltese are ambivalent about their country’s progress: They know that economic opportunities are more plentiful than they used to be, but they fear progress might be smoothing away the country’s distinctive edges. The skyline is dotted with cranes rising above the cathedral domes, and those cranes always seem to be hovering over the same sort of building: tall, rectilinear, and cut in clean angles. Malta is the most densely populated country in the EU, and the economic boom of recent years has intensified the pace of construction. Locals often complain of the dust from all of the building sites; when it rains, the drops sometimes hit windshields as small, powdery explosions—tiny puffs of brown smoke.

Competing real estate agencies line Sliema’s coast road, stretching for several blocks. Constantly changing listings for apartments and houses paper their windows. “There’s big demand, and the prices keep getting higher,” says Carl Peralta, director and founder of 77 Great Estates, one of the agencies.

Driving that demand is a new genus of Maltese resident that, Peralta insists, can easily be spotted in the cafes and restaurants of Sliema. Many are from northern Europe, and almost all are young—20s, maybe early 30s. They carry backpacks, they don’t drive cars, and they’re rarely spotted anywhere before 10 a.m. They work for the hundreds of internet gaming companies that have flocked to Malta in recent years. The companies offer the range of gambling services, from online poker and games of chance to sports betting.

In the early 2000s, only two online gaming companies could be found in Malta; now there are up to 300, and the sector accounts for an estimated 12 percent of the economy, according to the Malta Gaming Authority. Both the governing party and the opposition agree that the growth was a result of commendable foresight: In 2004, Malta became the first country in Europe to regulate online gaming, helping to legitimize an industry that previously stood on the fringes of respectability and legality.

The new arrivals who’ve bought citizenship through the passport program maintain a much lower profile than the gaming-industry workers. You can’t pick them out of a crowd on the street, and it’s difficult to even identify them in government documents. When Malta last released its annual list of new passport holders, it was maddeningly difficult to decipher; purchasers were listed in order of their first names, without a country of origin, and mixed among thousands of others who obtained their citizenship though birth or naturalization.

The Maltese press has discovered that the list of new citizens includes Russian oligarchs and even a woman who was suspended from the Vietnamese parliament for having dual citizenship, which is illegal in Vietnam. Roberta Metsola, who represents Malta in the European Parliament, suggests that many of the passport purchasers want nothing to do with Malta; they simply want the financial and travel access that an EU passport provides. “We’ve had cases of people arriving on a private jet, meeting a real estate agent, taking out a basement flat somewhere here for a year, never even seeing it, and leaving in the afternoon,” Metsola says.

Peralta, the real estate agent, says that rings true to him. Those who are buying passports, he says, know the minimum they must spend on housing—either €350,000 for a purchase or rental payments of at least €16,000 a year for five years. Meeting those minimum requirements, Peralta says, is often the only feature they’re specifically looking for in a property. “I know there are checklists they have that say they need to open the water taps once a month, or send a cleaner once a month,” he says. “But no one is living there.”

Jonathan Ferris speeds through Valletta’s darkened streets, jumps off his motorcycle, and walks briskly into the lobby of the Phoenicia Malta Hotel, where he finds a table in the noisy lounge. His features are lean, and he moves with a restless energy. His eyes scan the room, and he raises his voice just loud enough to be heard above the lounge singer, who is halfway through a slow and torchy version of Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird.

“I was the top man,” Ferris says, “the top investigator of financial crimes in the country. Type my name in the internet. All bloody hell comes up.”

The European Parliament is concerned enough about Malta to have sent an investigative delegation to the country multiple times this year. The committee’s report, issued recently, described an atmosphere of fear had settled over the country—and a sense that criminals could operate with impunity. Ferris believes his life during the past year perfectly represents the intersection of both phenomena.

He says that in 2017 his bosses at Malta’s Financial Intelligence Analysis Unit, the national agency tasked with policing money laundering, asked him to step aside from the investigation of the allegations involving Muscat’s wife and aides. He had told them he didn’t trust one of the known sources that had fed Caruana Galizia information regarding Michelle Muscat’s alleged ownership of the shell company—a source Ferris had investigated before and who, incidentally, was later discredited by the magisterial inquiry. Ferris’s bosses told him they believed his history with that source compromised his objectivity. That angered him, and he told his bosses that within 72 hours he could determine the true owner of the company that Michelle Muscat was allegedly involved in. He explained to them how he would consult tax returns, political party documents, and bank records. The next day, he says, he was fired and stripped of access to investigative documents and records. His firing further fueled suspicions against Muscat and his wife.

After Caruana Galizia was killed, Ferris says, he began to fear for his own life. He takes his bloodhound out for walks in the early morning, and several months ago he began to notice cars following him with the headlights off. “I decided, from now on, I’m always going to carry my gun around,” he recalls. Police officers now monitor his house for eight hours each night. “What good does it do? I don’t know, because for the rest of the 16 hours out of 24, I and my family are all alone.”

After Caruana Galizia’s murder a similar anxiety spread quickly among those seen as unfriendly to the government. Some of Malta’s neighbors pointed to that generalized unease as emblematic of the current state of the country. The European Parliament report described “systemized and serious deficiencies” in the rule of law in Malta, which had eroded the population’s general sense of security. Additionally, a police investigation in Italy has alleged that the Sicilian Mafia infiltrated companies in the online-gaming sector, using them to launder illicit funds.

When Muscat sat in front of European Parliament members during a plenary hearing to discuss the rule of law in Malta last June, he dismissed the allegations publicized by Caruana Galizia as politically motivated, setting a tone for his denials that he’s used ever since. His relaxed attitude—and particularly his periodic smiles—during the questioning rankled some of the politicians.

“You can laugh all you like, prime minister,” said Werner Langen, a German member. “But we will insist that you don’t get off scot-free.”

This past year was supposed to be Malta’s chance to showcase its economic gains to the outside world, to take a victory lap after years of growth. It assumed the presidency of the EU in 2017—a first for the country—and this year Valletta was named the EU’s Capital of Culture, another rotating title that was cast as a big deal for such a small country. Earlier this year Muscat went so far as to claim that national pride in Malta had hit an all-time high.

The country’s tourism authority kicked into high gear to take advantage of the promised attention. All sorts of cultural galas and grand openings were organized, and the National Museum of Archeology, a grand 16th century building in the middle of Valletta, became a nucleus for the celebrations.

One afternoon in April, tourists filed through the museum’s entrance and wound their way past exhibits that guided them along the country’s circuitous story. On the second floor, dozens of people entered the majestic Gran Salon, which centuries ago served as a banquet hall for the knights of the Order of St. John. Enormous tapestries, ancient and colorful, hung from the walls, and a small crowd gathered in front of a podium for a special event that had been organized just the day before. Scicluna, the minister of finance, stepped to the microphone.

“I’m very proud, and very pleased, to be the person to launch this national Anti-Money Laundering and Combatting of the Financing of Terrorism strategy and plan,” Scicluna said.

Despite the introduction, he didn’t appear to be particularly pleased to be delivering a speech denouncing money laundering, drawing more attention to a problem that he clearly sees as a threat to Malta’s reputation and livelihood. The reputational damage resulting from continued scrutiny from various quarters—the European Parliament, the European Banking Authority, Italian police, the U.S. Department of Justice—could trigger a backlash against the tiny country that might pose a real threat to its economic foundations.

As the investigation into Mafia involvement in Malta’s online-gaming sector continues, European lawmakers have several times proposed restrictions on cross-border betting, a change that would classify the services provided by many Maltese companies as illegal. Ana Gomes, a Portuguese parliamentarian who leads the EU commission investigating rule of law in Malta, has said the country’s low corporate tax rate is “anti-European” and saps billions in revenue from other member states. In March, the European Parliament voted to pursue a “tax harmonization” scheme that would create one common corporate tax rate applied throughout the EU. A U.K.-based nonprofit advocacy group, Tax Justice Network, issued a report estimating that such a policy would cut Malta’s tax base by more than half.

In the midst of these pressures, Scicluna stood at the podium and delivered a string of statements that should seem so self-evident that they’d never have to be uttered. “I’d like to say that Malta—and this is an important statement to make—is deeply committed to preventing, detecting, and prosecuting money laundering and terrorist financing activities. Financial crime threatens the safety of our society, the integrity of our financial system, and the stability of our economy.”

That economy, Scicluna hastened to add, was healthy and strong, and this year the International Monetary Fund’s executive board singled out the country’s “sound policies” as the root of its success.

When he wrapped up his remarks, the crowd in the Gran Salon filed out of the museum, where they joined the current of pedestrians flowing along Republic Street toward the Great Siege Monument, which sits in front of the main courts building in one of the city’s central squares.

Since last fall, people have been placing candles, flowers, and signs at the base of the monument as a makeshift memorial to Caruana Galizia. At least eight times since then, someone has swept away the items in the dark of night; each time, the flowers and candles and signs are quickly restored. Recently, a local governing council lobbied to ban the temporary memorial for good, arguing that it was time for the country to move on.

On this day, dozens of tourists stopped in front of the monument and faced the plaques that explained the historical significance of the statues. But none of them pointed their cameras up at the statues. Every one of them focused on the marble base and the makeshift memorial, and on the sign that read, “No Justice.”