“Did I make over a million dollars this year? Yes I did.”

Joshua Davis is among hundreds, maybe thousands, of creators who have made life-changing amounts of money from the non-fungible token (NFT) boom. But he didn’t make his mil selling profile jpegs of zombie gophers wearing polo shirts.

This feature is part of CoinDesk’s Culture Week.

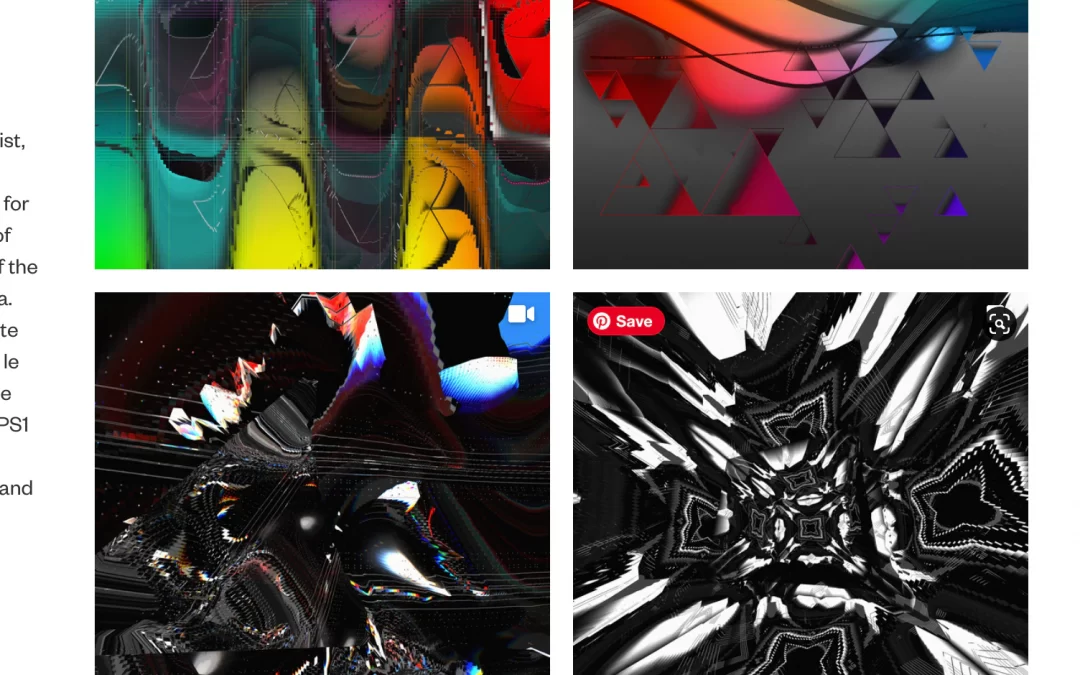

Davis founded Praystation.com in 1995 to display his art, part of a new wave of creativity then being unleashed by home computers and the World Wide Web. His works, at first composed largely using the Flash animation tool, consist of code that produces dozens, even hundreds, of related images by repeating a set of rendering commands, with randomly changing variables for features like color and line length.

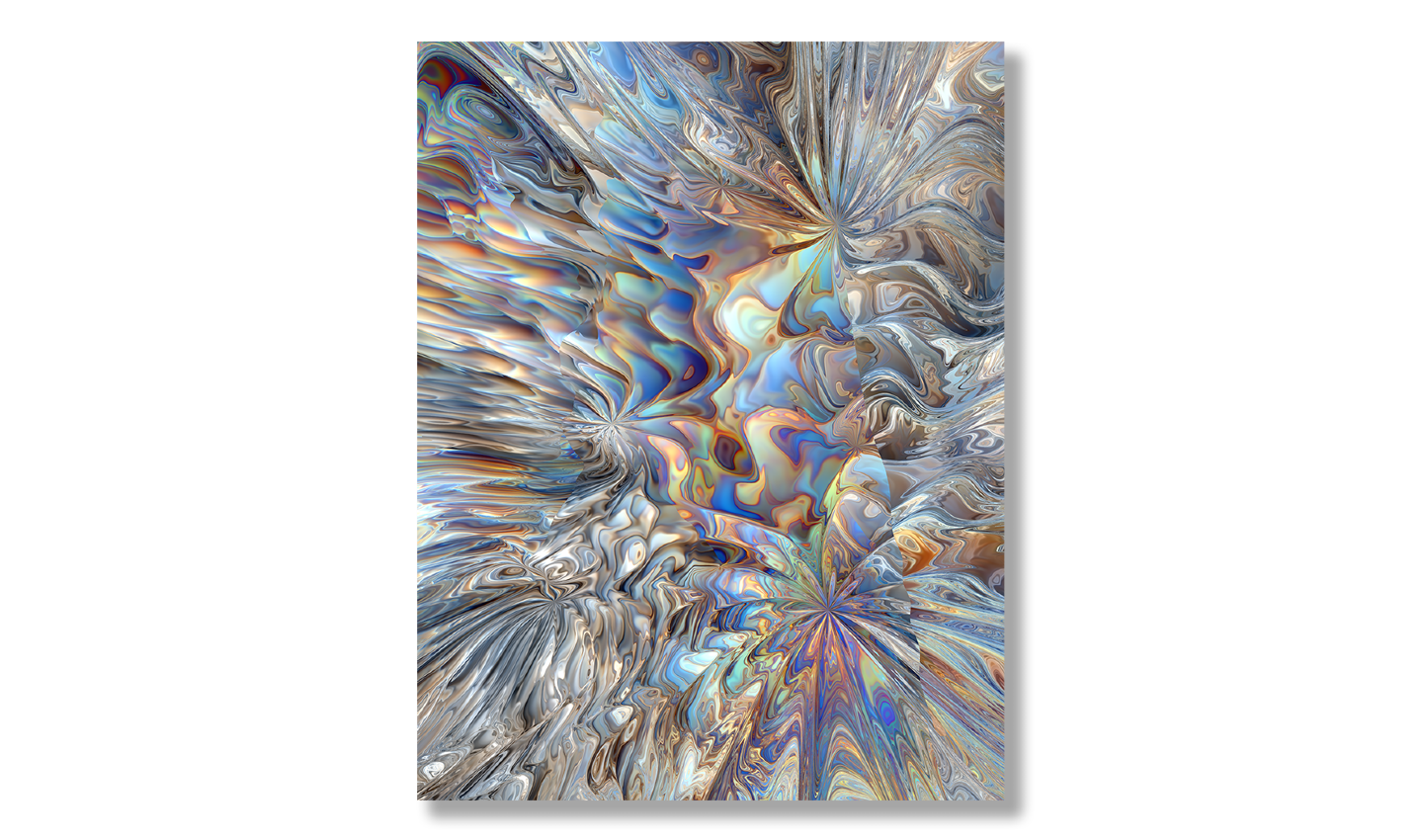

The images are abstract, noisy, sometimes unnerving. Davis’ work made him a respected digital artist decades before the first Ape got Bored, and one of the contemporary scions of “generative art,” an artistic tradition whose roots stretch back at least as far as the 1940s. In its modern form, generative art weds computer science with biology and physics to create images, sound or video based on randomized elements and parameters. The results are often fascinating, and just as often deeply strange.

But for decades, Davis and his contemporaries struggled with a very real problem: money. Because their art was nothing more than bits, there was no individual, unique object they could sell in the way one would a painting. Artists like Davis have sold prints and books, but they largely missed out on the kind of big collector paydays that other leading fine artists enjoy. That is, until NFTs came along.

“I never thought this would happen in my lifetime,” Davis says of NFT technology and its huge benefits for generative art. “I thought the next generation maybe would find a way to find value in digital art. I never thought digital art would be embraced as something you could assign provenance, collectability and scarcity.”

While headlines have focused on the speculative, trivial, sometimes silly applications of NFTs, the technology has truly transformed Davis’ very respectable corner of the art world. They’re giving an entire artistic tradition that had been ephemeral and conceptual the chance to join the fine art market on solid footing for the first time.

What is generative art?

If you’re an NFT fan, you might have heard the term “generative art” applied to “profile pic” NFTs like those Bored Apes, whose features are randomly selected based on a “rarity” algorithm. That makes Pudgy Penguins and Wonky Whales, believe it or not, descendants of path-breaking work by some of the most important artists of the 20th century.

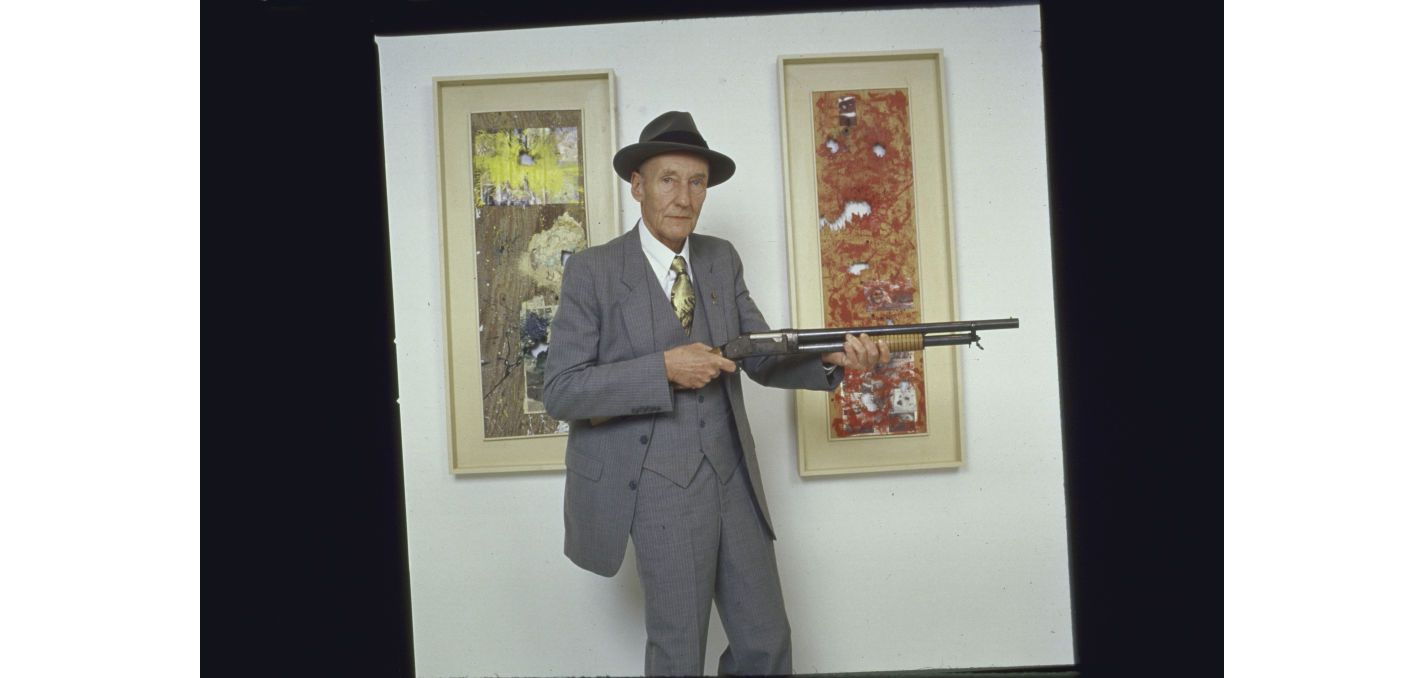

In my conversations with generative artists working today, one name came up again and again as a touchstone: Sol LeWitt. Starting in the late 1960s, LeWitt began producing large, geometrical wall drawings, not by drawing them himself but by writing detailed instructions that could be executed by anyone. Galleries still regularly present the works as interactive collaborations, with viewers themselves doing the drawing.

Joshua Davis says his “aha” moment as an artist was realizing the same logic could be applied more generally. “When an artist walks in front of a blank canvas, there are decisions that are made – the colors I use, the brush, the canvas, the kind of strokes I’m going to make … I could look at [Jackson] Pollock or [Jean-Michel] Basquiat – here are the kinds of strokes, the actions. Those actions, I could program.”

Other mid-century artists helped lay the foundations for generative art by taking cues from then-emerging computer technology. The Hungarian-French designer Victor Vasarely crafted rigid grids and 3D illusions that predated computer graphics by as much as half a century. The Dutch designer Karel Martens produced dozens of iterative sets of overlapping shapes. Among the first artists to actually apply a computer to art making was Grace Hertlien, who said other artists called her a “whore” and a “traitor” for using computational processes in art.

Other prominent creatives were exploring ideas of procedure and randomness alongside these visual pioneers. Starting in the mid-1940s, composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham began using “chance operations” such as flipping a coin to determine the length of a note. In the 1950s, the painter Brion Gysin and novelist William Burroughs developed the “cut up” method of generative writing, which produced new work by cutting up existing text and randomly rearranging it. (Burroughs was also strangely connected to early computing, as the heir of an adding machine empire).

These pathways represent the two big ideas being explored in generative art: chance and systems design. John Cage often subtracted his own intention from his work as a challenge to the romantic notion of artistic genius, as with his infamous “4:33″ – a composition made up, not of music, but of the random noises in a concert hall for four minutes and 33 seconds. Rather than seeking the precision and control of a Beethoven or Rubens, generative artists express themselves through the parameters of randomized systems.

“I think there’s something really beautiful to thinking about systems,” says Zach Lieberman, a veteran generative artist who teaches at the MIT Media Lab, co-founded the School for Poetic Computation, and has collaborated with author Margaret Atwood. “We can ask really complicated graphical questions, and by manipulating those parameters we can see, where does this parameter space take us … between 0.1 and 0.01, the difference can be really dramatic. I think there’s something really special in that.”

The digital explosion

These early analog works were ripe for expansion once personal computers put programming and graphical tools in the hands of the masses. As Davis recounts it, some of the most influential generative art of the 1980s and 1990s came not from galleries, but from hackers peddling stolen software.

“You would get cracked software,” says Davis, “And they’d include a [graphical] demo reel from the team that cracked it, and the goal was to do the most visually robust scene in the smallest number of bytes.” This was the era of dial-up internet, so the name of the game was to generate rich visuals, from flyovers of verdant landscapes to complex abstract shapes, from tiny blocks of hyper-efficient code running on the downloader’s machine.

“They’d be, like, 4 kilobytes,” says Davis. “Mind boggling.” As we’ll see, that focus on efficient coding has found new relevance with the arrival of NFTs.

This feature is part of CoinDesk’s Culture Week.

Though the arrival of the internet and home computing blew the creative doors open on generative art, artists still faced a major problem. “For years we’ve really struggled with, how do we sell this work?” says Zach Lieberman. “How do you sell a video, how do you sell an image? This thing that’s reproducible, it’s hard to tell how it fits in the gallery context.”

NFTs appear to have genuinely solved that problem. Generative artists even have their own dedicated NFT platform, Art Blocks, where they upload algorithms that buyers can “mint” iterations of. Art Blocks has generated hundreds of millions in sales, an immense windfall for long-suffering digital artists. A roving NFT gallery called Bright Moments, which emerged from Fred Wilson’s Union Square Ventures, mints pieces during live events, revealing iterations of work like Tyler Hobbs’ “Incomplete Control” to buyers in real time.

The technology isn’t without its critics and drawbacks, of course. Environmental concerns swirling around proof-of-work mining have impacted perception of NFTs, and Lieberman says they’ve become an issue in the art world.

“Some people say they’ll do proof-of-stake only,” he says. “And then there are people who hate this, including people I love.”

A related drawback is cost. Minting an NFT on the Ethereum blockchain can cost hundreds of dollars right now, which may be too big of an upfront investment for younger artists. According to Lieberman, many in the generative art community have turned to the Tezos blockchain for lower-cost experimentation.

NFTs beyond jpegs

As much of a breakthrough as NFTs have already been for algorithmic artists, their full potential remains to be explored.

“I’m really excited by artists who are experimenting with the fundamental form of what an NFT is,” says Lieberman. “Hacking at the layers of code.”

The starting point for that is a growing emphasis on storing everything on-chain. Many NFTs released at the height of avatar-mania were justly lampooned as nothing but links to images stored on web pages that could go down at any time. That’s a big step back from the pieces that pioneered the format, CryptoPunks, which are fully on-chain.

“I thought CryptoPunks were a brilliant example of generative art,” Art Blocks founder Erick Calderon, himself a generative artist, recently told ArtNews of his early exposure to NFTs. “Somebody wrote an algorithm that within a 24-by-24-pixel image was able to create 10,000 unique characters with a story.”

Read more: Why I Spent $29M on a Beeple – Ryan Zurrer

Artists like Deafbeef are pushing the boundaries of what’s possible for entirely on-chain generative work, working with constraints similar to those of the early 1990s demo scene. “The ideal drop on Art Blocks is between 5 and 20 kilobytes,” says Joshua Davis. “So you’re having to write the most elegant piece of code that has the most diversity in terms of color, variance, is it interactive … Being able to put code on-chain that keeps creating those moments when you go back is just tremendous.”

Other possibilities of NFT art are much weirder, and create options that artists have never really had before. For example, pieces can alter their appearance as they’re bought and sold on-chain, or through cryptocurrency interactions. The artist Rhea Myers, for instance, creates graphical works on Ethereum that users can alter by burning associated ERC-20 tokens.

Another frontier still to be explored is how to present generative art NFTs beyond your laptop screen. Davis sees interactivity as the killer app here, envisioning visitors generating art based on their own inputs through motion-tracking hardware. “I’m going to track your movement, and that becomes part of the generative art that gets preserved on-chain. You’re seeing your movements translated into some sort of artistic input, and at the end you get a video of your 45 seconds. I think we’re just at the start of what can be offered as a collectible.”

These novel tools are being discussed in a growing number of journals and podcasts dedicated to generative art. Outland is a home for thinky essays at the intersection of computation and cultural theory. Holly Herndon, one of the artists at the forefront of the movement, also co-hosts the Interdependence podcast, featuring discussions with generative and digital artists.

The existence of those platforms for exploratory pontificating also helps highlight the distinction between adventurous fine art like Lieberman’s 2020 “Future Sketches” and the more straightforward illustration and design approach behind many mainstream NFTs.

“I often think about art as [like] navigating through a new city. It feels like walking around late at night, it’s a little dark, you get lost,” says Lieberman. “The creative process is about navigating the unknown and known, or going back to familiar territory with new eyes. Design, on the other hand, always feels like a daytime activity. You have a map. You know where you’re going.”

Yes, it’s still about money

That experimental attitude may make the financial side of NFTs even more important for adventurous generative artists than for more commercially minded creators. Davis says this year’s cash infusion is going to give him time to focus on exploring the frontiers of his medium, rather than having to chase sidework to pay the bills.

But NFTs don’t just put digital artists on equal footing with traditional painters and sculptors – they actually sweeten the deal. If a painter in the traditional gallery world sells a piece for $35,000 and five years later it resells for $4 million, she doesn’t see any of that resale money. But NFTs can be designed to perpetually send revenue from secondary sales back to the artist.

“The first time my work was resold and I got 10% or whatever it was, that’s amazing,” says Lieberman. “That feeling of, oh my god, here’s this thing that happened between two other people, I was not involved and I received a percentage, that was mind-blowing. That’s never happened to me. It was a lightbulb moment.”