Every morning, Pavel Skazkin wakes up at the command of correctional officers while the Russian national anthem plays in the background. Four times a day, guards check on him.

The correctional facility where he lives is not as strict as the penal colony he was sent to at the age of 27, after he got caught with a package of marijuana and ecstasy. Inmates at his current residence can walk out of the guarded territory to attend their workplaces in a nearby town, as well as use internet-connected devices.

In the latter option he has found a creative outlet, a sense of purpose – and, thanks to the flourishing NFT market, extra income to supplement his inmate’s salary of $140 a month.

Skazkin, now 31, creates surreal digital art on an iPad and sells non-fungible tokens (NFT) of the works under the handle Papasweeds – a wordplay on his criminal charges, family story and self-reflection after four years of incarceration. His art NFTs, too, are a form of reflection on his life and the nature of the Russian penal system.

To help others suffering similar hardships, Skazkin has pledged to donate one-third of the proceeds from his NFT sales to Russia Behind Bars, a non-profit dedicated to aiding inmates and their families.

“I know how hard it is, both to be in prison and to wait for your family member to get out,” the artist told CoinDesk in a phone interview. “I’d like to help.”

Skazkin’s story is an unusually dramatic example of how the current wave of hype and speculation around NFTs sometimes provides new ways to support causes such as human rights, domestic violence victims and independent journalism.

Locked art

Skazkin started drawing his future NFT sketches while in the penal colony in Russia’s Bryansk region – 200 miles from his home in the Moscow area – where he was initially placed in 2017 after being sentenced to six years behind bars. All electronic communications and gadgets are forbidden in such facilities.

Three years into his term, Skazkin managed to successfully appeal for a lighter punishment and was transferred to the venue where he is serving his time now, also in Bryansk. And he immediately started turning his drawings into digital art, he said.

He sold his first prison-inspired NFTs for modest prices on Hic et Nunc, a lesser-known NFT marketplace that runs on the Tezos blockchain, which has lower transaction fees than the dominant NFT platform, Ethereum.

This is how Skazkin got into the Russian-speaking NFT community and joined the Telegram group of NFT Bastards, a loose group of artists that this year sold NFTs to help Russian online media outlet Meduza.

Read more: Russian Artists to Sell NFTs to Support Journalists Under Pressure

Then, NFT trader Ilya Orlov noticed the non-typical artist in the chat and thought he’d like to help.

“First thing we need to change [in Russia] is prisons,” Orlov told CoinDesk in a joint interview with Skazkin.

“As long as we’re torturing our own people this way, nothing can change for the better. We need to get people’s attention on that, especially now when the information [about torture in Russian colonies] got public,” Orlov added, pointing at the recent publication of blood-chilling video footage of inmates being tortured in one of Russia’s penal colonies.

Orlov is helping Skazkin to fund his NFT minting; with his inmate’s salary of about $140 a month, the artist can hardly afford network transaction fees (the so-called gas fees) for creating these tokens on the Ethereum blockchain. Therefore, a smart contract has been programmed to automatically split the proceeds from each NFT sale three ways: 33% will go to Papasweeds himself, helping him support his wife and three children, 33% to Orlov for his assistance and 33% to Russia Behind Bars.

Orlov said he believes Papasweeds’ prospects are huge. “In the West, people value and respect Russian pain and suffering, hence the popularity of Dostoyevsky,” he said. “I told [Skazkin], you get free, we apply for a U.S. visa and make you an exhibition in New York.”

Upon his release two years from now, Skazkin is planning to mint 72, or 66+6, NFTs, as written on his page on Foundation, a prestigious invite-only platform for NFT artists. Although 666 is the Biblical number of the beast, to Skazkin 66+6 is just a nice number, the artist told CoinDesk. He initially planned to do 666 NFTs until his prison term is over, but then realized he doesn’t have enough time until his scheduled release in 2023. So 666 turned into 66+6.

The weeds

Back in 2017, Skazkin, a not-too-successful web designer by trade, worked at an illegal online shop hosted on RAMP, a formerly popular darknet marketplace shut down by the Russian authorities the same year. One day, he was hired to pick up a package of drugs and pass it to sellers who would then divide the batch into smaller parts and deliver those to online buyers.

Skazkin was caught with that weed by the police and sent to jail for six years for drug trafficking. The prosecutor asked for a 10-year sentence, but Skazkin, a father of three, got six years.

After serving part of his term, Skazkin managed to litigate and win a lighter punishment, even though he had no attorney to help him draft court papers, he said. (His account was confirmed by Russia Behind Bars’ Olga Romanova.)

“I studied in the prison library, read the laws,” he said.

When asked about his nickname, Skazkin said it’s a portmanteau of several things. The nickname “papa” stuck to him after he became a father of three. “Weeds” is a double entendre: It refers to Skazkin’s drug-related crime; also, kosyak, the Russian slang for a bad mistake or a screwup is the same word as the one for a joint.

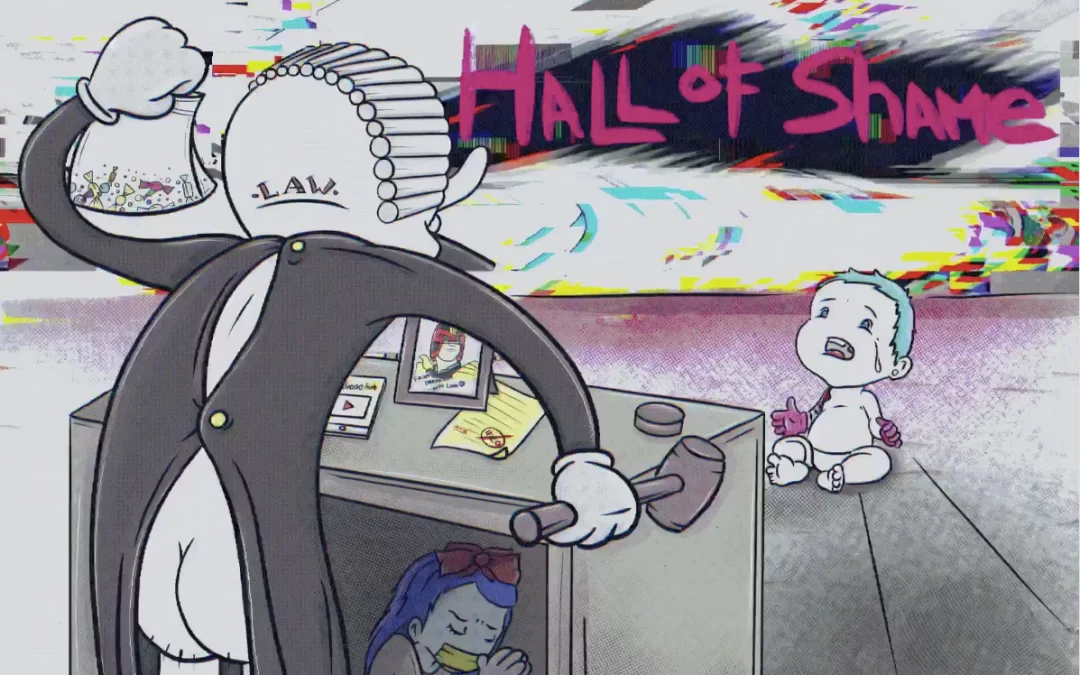

Skazkin is candid about his criminal charges and prison experience. He definitely ended up in prison for the right reason, he said. However, he believes his sentence was overly harsh. His first NFT work on Foundation, “Hall of Shame,” depicts a judge and a crying child in a courtroom – a metaphor of how he recalls his own trial.

“I felt like a kid being punished for the sweets he’d stolen, and there was nothing I could do. Whatever I had to say would sound like baby talk,” he recalls.

Spending several years in a Russian prison was a tough experience, but it changed him for the better, Skazkin said: “I got my brain in the right place. Got rid of many complexes, useless thoughts, became more aware.”

The lesson came at a steep price, though.

The penal colony near the city of Bryansk, where he served three years, is known as one of Russia’s cruelest correctional facilities, infamous for beatings and torture of inmates (links to articles in Russian).

“It was, you know, quite a school of humiliation,” Skazkin said.

Darknet education

It was working on the darknet that helped Skazkin to familiarize himself with the concept of crypto early on – back in 2017, he already had some bitcoin, he said.

In prison, he could only get news about crypto from print newspapers and magazines, or from the rare mentions on the Russian state TV the inmates were allowed to watch, or from his family members who would come to visit.

“In 2017, I saw bitcoin growing and was biting my elbows [because] I was in that place,” he said. In February of this year, Skazkin was reading Popular Mechanics magazine and saw a story about the famous meme-based NFT Nyan Cat, which sold for a whopping 300 ETH, worth about $590,000 at recent levels.

“I was like, what are these NFTs? OK, I know what crypto is, I had a bitcoin wallet, but this is also about drawing,” Skazkin said. He decided he would create his own NFT as soon as he got to the internet.

Olga Romanova, head of the non-profit Russia Behind Bars, said the organization has been raising money with crypto donations for five years now, and no less than 30% of all donations now come in crypto. Russia Behind Bars is accepting bitcoin, ether, litecoin and XRP, its website says.

NFTs, however, are something new for the advocacy group.

“Can’t say I understand digital art. But I understand people who got in trouble but weren’t broken, keep growing and trying to support their families, as well as other prisoners,” Romanova said: “This doesn’t happen very often and this alone deserves attention and support.”

Read more: Russian Activists Use Bitcoin, and the Kremlin Doesn’t Like It