After the liquidity crises in 1998 and 2008, you might expect that market participants would learn their lessons about derivatives, leverage, non-transparency, and runaway banker greed. That never happens. After both crises, policymakers allowed banks to revert to their old tricks on an even larger scale. (That’s partly because the policymakers often go to work for large banks after they leave government to line their pockets before the next crash. Think of Republican Senator Phil Graham becoming Vice Chairman of UBS or Democratic Treasury Secretary Bob Rubin becoming head of Citigroup. There are many other examples). Today the “too-big-to-fail” banks are bigger and more concentrated than ever. So, it’s no surprise that asset bubbles are emerging that will make the 2008 crisis look like a stroll in the park on a sunny day. In 2008, the capital markets were almost wiped out by defaults in subprime U.S. residential mortgages. In the article below see how this time the property asset bubble is global, including high-end real estate, commercial office space, and warehouse facilities. (Subprime is under control, but that’s small compared to prime housing and commercial real estate. It’s never exactly the same twice.) This real estate bubble is in addition to all of the other bubbles in stocks, emerging markets corporate debt, high-yield, Chinese credit, and developed economy sovereign debt. Cash, gold, and silver may be the only true safe havens when the next crisis hits, probably soon. – Rickards

Fears of a ‘massive’ global property price fall amid ‘dangerous’ conditions and market slow-down

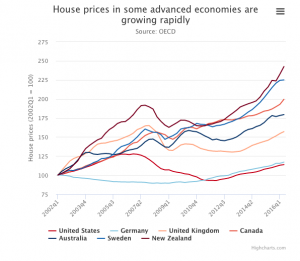

Property prices have climbed to dangerous levels in several advanced economies, raising the risk of massive price falls if markets overheat, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Catherine Mann, the OECD’s chief economist, said the think-tank was monitoring “vulnerabilities in asset markets” closely amid predictions of higher inflation and the prospect of diverging monetary policies next year.

Ms Mann said a “number of countries”, including Canada and Sweden, had “very high” commercial and residential property prices that were “not consistent with a stable real estate market”.

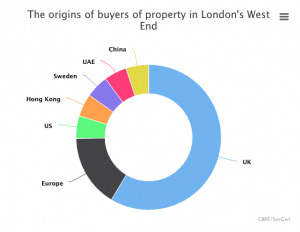

She also said property price falls in Britain following the vote to leave the EU could “be good for the UK” if the adjustment is borne mainly by foreign investors.

“We’ve already started to see some changes in real estate prices in the UK, [particularly in] the London market,” said Ms Mann.

“[What’s] interesting in terms of the implications for the UK economy is who bears the burden – who bears the adjustment cost. If it’s a non-resident then lower house prices could actually be good for the UK.”

The warning comes as research by Countrywide reveals that the number of homes sold in the UK for more than the asking price has tumbled in the last year.

In January 2016, 41.5pc of homes for sale in London were sold above the asking price. But this fell to just 23pc in November. Nationally, the fall was less steep: from 29.8pc in March to 23.1pc in November.

The data suggest that the UK housing market could be at an inflection point with activity slowing throughout 2016, particularly in the capital, as sellers accepted lower offers while buyers deserted the market amid uncertainty over Brexit.

While prices did not fall across the country last year, there was a slowdown in activity as people chose not to buy a home. Johnny Morris, head of research at Countrywide, said: “There isn’t the same level of competition in the market now.”

The Royal Institution of Surveyors reported that the number of new buyer inquiries has been at very low levels in the second half of the year. The number of new properties on the market has also been at record lows, helping to prop up prices.

Mr Morris added: “We expect prices to fall next year as this slowdown works through the system. Generally the first thing to change will be the number of transactions, and then after the gap between what people will pay and how much people will accept opens up quickly and takes a while to close. Sales slow, and then there is a price adjustment.”

The EU’s financial risk watchdog recently warned that eight countries, including the UK, had property markets that risked overheating in the environment of low interest rates.

The Bank of England also cautioned last month that the improvement in household finances seen since the 2008 crisis “may have come to an end”.

The OECD’s Ms Mann said countries such as Canada, New Zealand and Sweden had all seen rapid increases in house prices over the past few years.

While many of these countries have already introduced policies designed to reduce financial stability risks, including forcing buyers to find larger deposits and imposing borrowing limits, Ms Mann suggested that a house price crash would also reduce household spending.

The OECD’s latest economic outlook warned that an initial price correction in overvalued property markets “could be magnified by fire-sales” if investors had been “betting on continued price gains due to monetary policy support”.

Ms Mann said the OECD was also monitoring the potential impact of a stronger US dollar on emerging market economies, particularly those with large shares of dollar denominated debt.

These countries could see the cost of servicing their loans rise sharply if their currencies depreciate against the greenback.

“The potential monetary policy divergences until 2018 are pretty big, and that does create vulnerabilities for emerging markets,” she said.

While many corporations that borrowed in dollars and exported to countries paying in the US currency had a “natural hedge”, she said the OECD research next spring would examine the vulnerabilities facing companies that primarily served domestic markets.