‘The way you use the phone is a proxy for the way you live’

Financial institutions, overcoming some initial trepidation about privacy, are increasingly gauging consumers’ creditworthiness by using phone-company data on mobile calling patterns and locations.

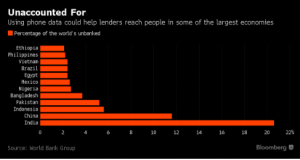

The practice is tantalizing for lenders because it could help them reach some of the 2 billion people who don’t have bank accounts. On the other hand, some of the phone data could open up the risk of being used to discriminate against potential borrowers.

Phone carriers and banks have gained confidence in using mobile data for lending after seeing startups show preliminary success with the method in the past few years. Selling such data could become a more than $1 billion-a-year business for U.S. phone companies over the next decade, according to Crone Consulting LLC.

Fair Isaac Corp., whose FICO scores are the world’s most-used credit ratings, partnered up last month with startups Lenddo and EFL Global Ltd. to use mobile-phone information to help facilitate loans for small businesses and individuals in India and Russia. Last week, startup Juvo announced it’s working with Liberty Global Plc’s Cable & Wireless Communications to help with credit scoring using cellphone data in 15 Caribbean markets.

And Equifax Inc., the credit-score company, has started using utility and telecommunications data in Latin America over the past two years. The number of calls and text messages a potential borrower in Latin America receives can help predict a consumer’s credit risk, said Robin Moriarty, chief marketing officer at Equifax Latin America.

“It turns out, the more economically active you are, the more people want to call you,” Moriarty said. “That level of activity, that level of usage is what’s really most predictive.”

The new credit-assessment methods could allow more people in areas without bank branches to open accounts online. They could also make credit cards and loans more accessible and prevalent in some parts of the world. In the past, lenders mainly relied on bank information, such as savings and past loan repayments, to judge whether to let someone borrow.

Some of the data financial institutions are using come directly from interactions with potential borrowers, while other information is collected in the background. FICO’s partner EFL sends psychological questionnaires of about 60 questions to potential borrowers’ mobile phones. With Lenddo’s technology, FICO can check if users’ phones were physically present at their stated home or work address, and if they are in touch with other good borrowers — or with people with long histories of fooling lenders.

“We see this as a good opportunity to explore that type of data for risk assessment, as a viable means of extending financial inclusion,” David Shellenberger, a senior director at FICO, said in an interview.

Juvo’s Flow Lend mobile app uses data science and games — like letting users earn points — to build real-time subscriber profiles, to let C&W personalize lending criteria and provide immediate credit extensions. Prepaid customers can request credit advances for airtime and data. Denise Williams, a spokeswoman for C&W, didn’t immediately return a request for comment.

Getting Permission

In most cases, consumers must grant permission for their telecommunications records to be accessed as part of their risk assessment. One reason it’s taken the credit-risk industry some time to work out agreements with phone carriers or their representatives is because of negotiations over how to best protect client privacy.

Companies are also concerned about making sure they don’t make themselves susceptible to claims of bias. By checking phone records to see if a credit applicant associates with people with a poor track record of repaying loans, for example, lenders risk practicing discrimination on people living in disadvantaged neighborhoods. In addition, to comply with the Fair Credit Reporting Act in the U.S., a data provider must have a process in place for investigating and resolving consumer disputes in a timely manner — something that telecommunications carriers abroad may not offer.

Several large phone companies contacted by Bloomberg declined to comment about whether they share data with financial institutions, and few of the startups or financial companies were willing to disclose their telecommunications partners.

Mirror of Life

Startup Cignifi, which helps customers like Equifax crunch data on who phone users are calling and how often, works with phone companies like Bharti Airtel Ltd.’s unit in Ghana. Cignifi scores some 100 million consumers in 10 countries each month, said Chief Executive Officer Jonathan Hakim. Banks typically use such assessments alongside other evaluations to decide whether to grant a loan. Airtel didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“The way you use the phone is a proxy for the way you live,” Hakim said. “We are capturing a mirror of the customer’s life.” His company collects phone data — such as whom the potential borrower is calling and how frequently — from partners like Airtel Ghana, and crunches it for customers like Equifax, as well as marketers. It scores some 100 million consumers in 10 countries each month, Hakim said. Banks typically use such assessments alongside other evaluations to decide whether to grant a loan. Cignifi always gets customers’ permission to use data, he said.

EFL’s questionnaire approach is already used by lenders in Spain, Latin America and Africa. More than 700,000 people have received more than $1 billion in loans thanks in part to its data, CEO Jared Miller said in an interview.

EFL’s default rate varies by country, from low single digits in India to low double digits in Brazil, Miller said. To account for the risk, lenders in Brazil charge much higher interest rates, he said.

Startups like Lenddo, Branch and Tala have collected several years’ worth of data to prove that their methods of using mobile-phone data work — and that customers flock to them for help. Started in 2011, Lenddo, for instance, spent 3 1/2 years giving out tens of thousands of loans, in the amount of $100 to $2,000, in the Philippines, Colombia and Mexico to prove out its algorithms. Its average default rate was in the single digits, CEO Richard Eldridge said in an interview.The company stopped offering lending in 2014, and stepped into credit-related services to financial institutions and banks in early 2015. Embedded into banking mobile apps, it can collect data on users with their consent. The company’s revenue is up 150 percent from last year, Eldridge said.

“The market is changing,” Eldridge said. “More and more people are seeing examples around the world of how non-traditional data can be used to enter into new market segments that couldn’t be served before.”