Finnish technology group Wärtsilä is set to deliver a 15-MW solar PV plant in Burkina Faso — creating Africa’s largest thermal-solar PV hybrid power plant.

The solar PV development will be integrated with an existing 55-MW Wärtsilä thermal plant (running on heavy fuel oil), to power IAMGOLD’s Essakane Mine, 330km northeast of the Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou. The plant is scheduled to be operational early next year.

Renewable Energy World spoke with business development manager, Jerome Jouaville, of Wärtsilä Energy Solutions, about the project and prospects for hybrid power plants.

“The project has been motivated by an appetite to lower operating costs via reducing fuel usage, but also by a desire to reduce CO2 emissions.”

Wärtsilä estimates that the solar PV addition will enable a reduction in fuel consumption of approximately six million litres per year, and reduction in annual CO2 emissions of 18,500 tons.

Jouaville continued: “It’s not an uncommon situation. In fact, we see many potential customers interested in this kind of hybrid solution, particularly over the African continent.”

Energy solutions provider Aggreko is also optimistic over hybrid generation — a solution it provides via turnkey solar-diesel packages.

This year, Aggreko signed a 10-year contract to deliver a solar-diesel hybrid to power mining operations for Nevsun in Eritrea. The hybrid will feature 22 MW of diesel and 7.5 MW of solar-generated power.

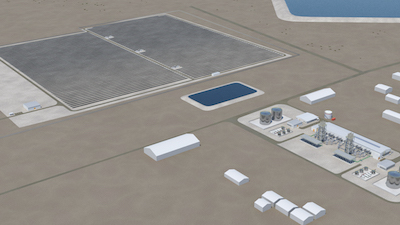

A rendering of planned solar PV field at Wärtsilä’s existing 55-MW thermal plant. Credit: Wärtsilä

Karim Wazni, Aggreko’s director of business development, renewables, told Renewable Energy World: “Hybrid generation is about achieving the best of both worlds.”

“Combining thermal power plants with solar or wind power, helps us bring the reliability, availability and flexibility of thermal power plants together with the low cost of electricity derived from renewable energy sources,” Wazni said.

He added that an additional benefit is reducing customers’ exposure to fluctuating commodity prices [of fuels].

Key to a hybrid project is success at the point of interface between the thermal and solar PV plants — something achieved through control systems, according to Jouaville.

“In order to successfully introduce solar PV, and offset some thermal generation capacity, we need to design and ensure that any time we push solar PV, we still have enough spinning reserve in the system to meet [the mine’s] base demand (of roughly 40 MW) even in the event of cloud-cover, or engine shutdown,” Jouaville said.

To this end, Wärtsilä is adapting its diesel engine operating system to accommodate solar PV generation.

“The system will manage loads and outputs, and control engines according to solar PV output to ensure we meet demand whilst keeping enough spinning reserve in the system,” Jouaville said.

Noting that the mine is not grid-connected, Jouaville added: “the priority for us is to deliver something that avoids jeopardising mining operations.”

Indeed, a perennial concern for energy intensive industries — and cause for reluctance to switch to renewables, in spite of potential economic gains — is sustained, reliable power supply. It’s a need that jars with intermittency of renewable power generation.

Nevertheless, Wärtsilä is confident.

“Hopefully, we will demonstrate the success of the hybrid technology with this project,” Jouaville said.

A stepping-stone to renewable powering industry to be sure, but with the timeline for taking all conventional thermal plants offline stretching out over decades to come, hybridization represents a promising interim solution.

“I believe we can replicate this kind of solution over many more situations where we have a combination off grid customers, long life of project, availability of land, and relatively high price on fuel – factors on which the economics of the business case relies,” Jouaville said. “In this case, the PPA is for 15 years.”

Considering the circumstances, the notion of adding battery storage, to enhance plant resilience and further lessen reliance on engines, is logical.

Jouaville agreed, saying: “Battery storage is something we’re considering for the next step [at Essakane]. There’s no technical problem, but we need to understand the battery performance requirements carefully.”

Aggreko has a similar outlook.

“Energy storage is a major player in the thermal-renewable combination,” Wazni said. “Adding energy storage to our hybrid power plants allows us to further increase the amount of solar power that can be integrated, while preserving the power quality and reliability, thus displacing more fuel consumed and reducing the costs for our customers. Energy storage also benefits the operation of the thermal plants by allowing them to run more efficiently.”

He added that overall, “we strongly believe that energy storage is an asset that can unlock tremendous value in many power projects.”

The hybrid-plus-batteries ambitions are reflected in strategic moves taken on behalf of each company. Wärtsilä recently acquired Greensmith Energy, a U.S.-based provider of grid-scale energy storage software and integrated solutions; while Aggreko acquired Younicos, a provider of integrated battery storage systems.

Jouaville observed: “Now Greensmith Energy are part of our family, I expect we’ll see more efforts to deliver battery projects. Hybrid thermal-solar PV is a great combination, but adding batteries is an even more exciting prospect.”

Lead image credit: Wärtsilä