This week, when the team at MIT Technology Review put me into a fireside chat with journalist Charlotte Jee during their Emtech MIT conference, the assigned title for the session – “Demystifying Decentralized Finance” – got me thinking.

It occurred to me that before we demystify DeFi, or for that matter the wider ecosystem of blockchains and digital assets, we need to first demystify traditional finance (TradFi).

Most people don’t have a solid understanding of how our capitalist system of payments, credit and asset transfers works. Getting to that understanding, I believe, requires looking into the deep historical roots of money and the social system of trust that has evolved around it. Only then can we develop a framework for talking about the traditional financial system and how the crypto industry seeks to disrupt it.

You’re reading Money Reimagined, a weekly look at the technological, economic and social events and trends that are redefining our relationship with money and transforming the global financial system. Subscribe to get the full newsletter here.

That’s what I’ll attempt to do with this column. First, I’ll categorize what I see as the architectural components of the traditional, centralized, fiat- and banking-based financial system, explaining how each came into being and the purpose it serves. Then I’ll map those components to their equivalents in the new, decentralized, crypto- and smart contract-based system.

A caveat: This is just one way of looking at this issue. It inevitably will have inconsistencies and contradictions. Feel free to email me with feedback, especially if some of my analogies and explanations are off.

The Money Stack

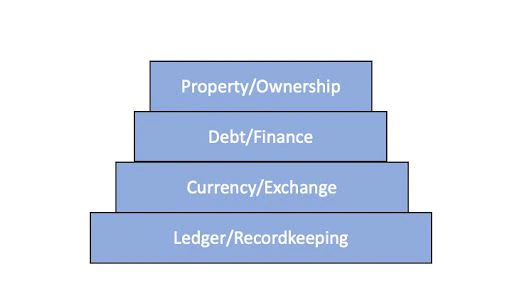

This framework starts with what I’m calling the “money stack” – no, not a stack of money, but an analog to the idea of a software stack.

Let’s look at each part of the stack, its historical antecedents and its role in the financial system.

The Ledger

Historically, the accounting profession has been the butt of jokes, a byword for “boring.” But the humble ledger-keeper is actually the foundation of human society.

It is no coincidence that the very first known examples of writing are the cuneiform records displayed on clay ledger tablets from ancient Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization. One of those tablets includes what is thought to be the very first name ever recorded: that of a Sumerian accountant by the name of Kushim.

To create a functioning system of exchange, one in which people across a larger community than just a small village could enter into contracts for trading goods and services, societies needed a trustworthy system of record-keeping to keep track of the delivery and settlement of those agreements. That’s what those ancient tablets enabled.

The technology for recording and storing those transactions has, of course, evolved tremendously from clay tablets to giant data farms. But in TradFi, the core governing principle for creating and keeping that trustworthy record hasn’t changed: it’s centralized, maintained by a trusted third party. Once it was Sumerian accountants like Kushim. Now it’s institutions such as banks, internet platforms and applications, or government agencies.

Currency

The true “money” part of the money stack emerged alongside the accounting tablets, at least in the form we currently recognize: currencies. Currencies gave people a medium of exchange, a commonly recognized unit of account with which to measure the worth of a good or service and store of value that can be converted in the future into those things of real value.

To me, money is best understood as a social technology. It’s a system that we all collectively believe in, one that requires a shared foundation of trust in the commonly recognized value of the currency. Getting that trust to scale across large communities required coordination. So, in the absence of a decentralized governance system to achieve that, the state seized that role. The relationship between government and money was formed early on.

A big leap in the technology of money occurred in the late 15th century when the Medici family took double-entry bookkeeping, a version of ancient ledger-keeping first developed in Arabia, and applied it to banking. That enabled a massive scaling of the payments and exchange function of money as it was no longer dependent on transfers of the underlying physical currency. It also forged a deep, symbiotic relationship between banks and the issuers of that physical currency, creating two sides of a centralized system of money.

Debt

Those same banks powered the development of credit. As they became pivotal to monetary systems, they began to accumulate society’s savings, amassing from people with surplus funds a giant pool of otherwise dormant liquidity to repurpose into loans for those with a deficit of funds.

Out of this grew a complex machine for generating credit, a system of interlocking institutions driving economic activity and feeding value back into the banking system in the form of savings. It is the fractional reserve feedback loop that is the basis for most of the money that circulates in our economy. That system now includes a vast array of non-bank investors, lenders and other institutions that power global credit.

Unchecked, this machine inevitably fueled crises as investment bubbles grew and then burst,

which led to the formation of central banks and a complex financial regulatory framework that imposes rules on the centralized entities that profit from that system.

Property

The evolution of a more complex economy also required a more complex legal framework for how human beings defined ownership of, first, goods, land and other physical property, and then, contractual rights to services and financial claims.

Property rights were formalized in the form of certificates and deeds in which a certifying authority – such as a land title office – attested to a person’s ownership of the property in question. An important extension of that was the creation of share certificates, which certified an investor’s claim of partial ownership in a limited stock company and their rights to future profit distributions.

Defining rights in this way gave early limited stock companies such as the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company the capacity to mobilize vast amounts of capital.

These days, electronic records rather than paper certificates are used, and they are typically managed by custodial banks on behalf of investing institutions.

The Decentralized Money Stack

The core problem with the TradFi money stack is that all of its components require participants in the system to trust a centralized entity. Someone or some institution must be trusted to keep the ledger, to issue the currency, to coordinate the conversion of short-term savings into longer-term loans and to certify people’s rights to property.

That trust imperative implies that the centralized entity has the capacity to act in its own interests against those of the users of the system. For that reason, society has developed a complex nexus of laws, regulations, accounting and auditing procedures to provide people with the confidence they need to use these services. All of that adds friction to our transactions and, ultimately, burdens the economy with massive costs.

This is where the decentralizing, disintermediating promise of cryptocurrencies, blockchains, digital assets and smart contracts comes in.

These technologies are coming together to forge a decentralized version of the money stack. Here’s how it maps out:

Ledger = blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum

Currency = bitcoin the currency, ether and/or other cryptocurrency payment vehicles

Debt = DeFi

Property = Non-fungible tokens (NFTs)

We have quite a ways to go before this system can fully integrate and scale to the point where it is the default model for global capitalism.

One step in resolving that will be to figure out which parts of the system will still require the engagement of new or traditional centralized entities, and which parts can be handled by permissionless tokens, blockchains and smart contracts. Determining what role is to be played by governments and regulation is also a challenging work in progress.

However, if we can come up with a common understanding of how this new system uses different methods to achieve similar outcomes to that of the old system, this development process will be less torturous. The decentralized money stack is my modest attempt to help in that effort.