Some really interesting developments are taking place in the Indian solar space. Module prices are hardening and there is talk of Discoms reneging on previous high tariff power purchase agreements (PPA) in light of declining tariffs, while developers are reportedly seeking to exit low tariff commitments in light of rising module prices. It’s all happening there!

In such a dynamic and fast evolving eco system, it’s a good idea to step back and address value and valuation — after all, a solid understanding of those constants in the context of solar in India is a handy beacon that guides through still and choppy waters alike.

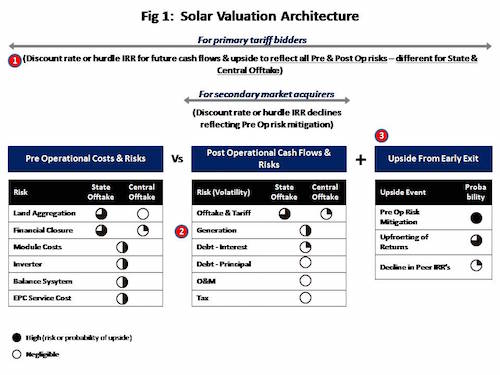

Figure 1 below provides an illustrative view of solar valuation architecture in tandem with accompanying risks and upside. For primary developers, the key objective of any valuation exercise is to determine tariff that they should bid. Viability of this tariff should be assessed in relation to pre-operational costs and associated risks vis a vis post operational cash flows (and risks) as well as the potential for upside from an early exit rather than holding the project for the 25-year life of the PPA. Subsequent discounting at the project’s risk reflective cost of capital — which is also the appropriate hurdle internal rate of return (IRR) — provides the answer to the million-dollar question: “How much should I bid?” (Unit tariff for primary developers, total acquisition cost for secondary market developers.)

A lot of any valuation exercise is just simple math, but many models do not adequately cover three fundamental areas which are most critical for tariff or value decision making

A lot of any valuation exercise is just simple maths, and indeed solar lends itself to simplicity in financial modeling like no other generation source. In this context, the fall in tariffs as a (partial) result of factors, such as fall in input (module etc.) costs and decline in interest rates, has been well-documented and these elements are fairly straightforward to model. What is not adequately covered are three fundamental areas which in my opinion are the most critical when it comes to tariff or value decision making and which typically receive little or sometimes even no attention at all in many financial models.

#1: Spread in Cost of Equity (or Hurdle IRR) Between Central and State Discom Offtake

I have written at length about the relationship between Cost of Equity and IRR as well as my view that for operational central offtake (NTPC/NVVN) solar projects the correct hurdle IRR should be built from ground up starting with NTPC’s own cost of borrowing and not derived from some arbitrary thermal derived benchmark. Given that these projects represent zero land aggregation risk (solar parks) and as the tariff payments themselves are arguably senior to the offtaker’s own debt service payments, a small margin on top of cost of borrowing can be a justifiable hurdle rate — which is why tariffs for central offtake are where they are today. It is here that the risk profile of state Discom offtake diverges. On top of the clear risks surrounding land aggregation (which some developers are unfortunately dealing with as I write this) there is also the credit profile of the state Discoms to consider.

As I have also pointed out in another article, the Ministry of Power’s annual “State Distribution Utilities Integrated Rating” does not actually publish “credit ratings” (which is an assessment of an entity’s ability to meet its financial obligations) but rather “gradings” reflecting financial and operational health. What does this mean for determining cost of borrowing for state Discoms? It turns out that getting solid guidance on this is not so straightforward.

For one, to the extent that certain Discoms have historically accessed the bank debt market, it has mainly been with public sector banks, and we all know how those loans have turned out. The pricing and appetite of UDAY (the central government’s big bang program to nurse state Discoms back to health) mandated bond refinance of those loans and is a poor guide. The bonds are state government issued (vs. Discom) and the very fine “across the board” central government mandated 75bps spread at issue over 10-year central government securities belies critical differences in even state specific credit quality. The subscribers as such to these refinance bonds are also no big surprise.

Guesswork on hurdle rates is not good enough anymore; in a competitive tariff bidding environment, models need to take into account the extremely wide spread in true borrowing costs between central and state offtakers

The real test would be if these Discoms were to go out to the private bank/capital markets to assess and price risk appetite for new “no strings attached” credit. With this background, it would not be an exaggeration to say there are some Discoms whose true cost of borrowing could be double or even more of what it costs NTPC to raise money. On top of that there is the land aggregation risk, which persists irrespective of credit rating. That means that all other things remaining constant (module prices, irradiation, etc.) a valuation model should result in state Discom tariffs that are always meaningfully higher than for central offtake and in certain cases double or more (tariff and IRR are not exactly linear in relation, but that’s an altogether separate topic).

It is in this context that while central offtake tariffs are not necessarily irrational, there is a danger of state Discom offtake tariffs flirting with irrational territory as we have seen in 2016 when certain state tariffs appeared to breach comparable central tariff levels. A critical element of any financial mode has to be a detailed build-up of each project’s independent cost of equity starting with a realistic assessment of each offtaker’s credit profile. Guesswork on hurdle rates is just not good enough anymore.

#2: Predicting Generation

One often hears folks say that for solar, top line is everything, which is a pretty sensible way of looking at it. The solar top line is a function of three elements, namely, the amount of sunlight falling on the location where the plant is located (global horizontal irradiance or GHI), the efficiency of the plant in converting GHI into electricity (performance ratio or PR), and the offtaker actually paying for the electricity thus generated. The risk associated with the last element is reflected in point No. 1 above, while the risk associated with lower than expected PR should ideally be contractually mitigated. It is risk associated with the first point regarding GHI that needs to be adequately addressed in a financial model as this is the base resource data from which everything else flows.

In a reverse auction environment for tariff discovery, using aggressive or conservative GHI estimates can both be dangerous

There are a few sources, such as Meteonorm and Solargis, which provide GHI data and recently even the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) has begun providing the same. However, this GHI data provided by each source differs even for similar confidence levels. Under the circumstances there is sometimes a tendency to go with “the most conservative (low GHI) number.” In a reverse auction environment, the concepts of aggressive or conservative GHI estimates are equally dangerous — use a conservative GHI number and one is likely to miss out altogether on capacity by bidding too high, while using aggressive GHI numbers will result in lower than expected generation. What is critical is to identify the GHI source and probability that most accurately reflects actual on-the-ground pyranometer readings in the future.

Recent reports of pollution posing a threat to solar returns need to be evaluated in this context. To the extent that predictive GHI figures take pollution into account then the solution is just a more robust O&M process, which won’t necessarily break the bank. However, if on the ground pyranometer readings for GHI are far below what has been estimated at the time of tariff bidding, then I’m afraid there is a pretty big problem for developers — and an even bigger lesson for those bidding for new capacity.

However one looks at it, a realistic assessment of GHI forms the backbone of any financial model and even small variances can have a big impact both in real or opportunity cost terms. Definitely something worth focusing on in any financial model.

#3: Probability of Upside

One of the principal differences between a normal company and a project special purpose vehicle (SPV) is that the latter has a fixed and finite life or cash flow stream. With this in mind there is a clear tendency to evaluate project economics on the basis of annual post tax cash flows to equity holders generated over the course of the entire project SPV life — what I like to call a “develop and hold approach.” This approach to valuation is a remnant of a past where energy developers did not see a broad-based secondary market for their projects. Both because the Infrastructure Investment Trust (InvIT) regime had not been established as well as the fact that only a limited band of financial investors actually had an appetite for the complex operational risk and return profile of these projects.

Adding to the above, discounting post tax cash flows to equity holders itself is a somewhat flawed approach to evaluating project SPV returns for two reasons:

- Under a corporate umbrella, shareholders would have to pay an additional c20 percent dividend distribution tax to get their hands on these cash flows

- A post tax cash flow based IRR evaluation works better for a company with nonfinite life as it does not necessarily have to distribute surplus cash to shareholders to crystallize value but can reinvest this to grow the business — a course of action outside the scope of possibility for project SPVs, which are constrained in reinvesting surpluses both by project loan covenants and by the very staggered nature of necessary investments themselves

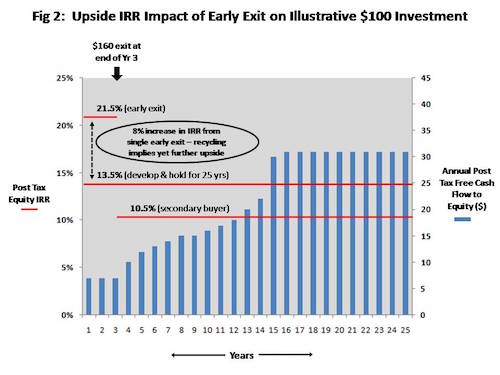

All this has changed with solar and InvIT — a complementary match like no other that allows financial investors to access low operational risk solar projects and receive dividends tax free in their hands. Okay, but does divesting a project well before the natural life really have a big impact on uplifting returns for the developer? Absolutely, and how! Figure 2 below studies this impact using illustrative cash flows to equity holders over the 25-year life of a solar project against a $100 up-front investment. These upward sloping annual cash flows are typical even in case of equalized principal repayments due to the interplay between interest, depreciation and principal and the fact that the latter is not tax deductible. Finally, the flattening out of these cash flows year 16 onwards is a result of an assumed 15-year tenor for the loan.

By investing $100 and holding the project SPV over the 25-year life period, the developer’s equity IRR is 13.5 percent. However, if a buyer steps into the picture at the end of year three and acquires the project for $160, the return to the primary developer dramatically increases by 8 percent to 21.5 percent. And keep in mind that this is not the end of the story for the primary developer. Upfronting means that this amount can be reinvested multiple times again over the 25-year life cycle — so in reality the real return figure is immensely even more attractive.

So why would a secondary buyer acquire the above project at a discounted 10.5 percent IRR? Three reasons.

First, as the project SPV is execution risk mitigated, a certain discount in required returns is to be expected. Second, there is ample scope to significantly bump up this discounted number for the secondary buyer by refinancing at a much lower rate via (e.g., bond market) as well as upside from additional financial structuring (read additional debt at HoldCo InVIT level). Third, these are “real” cash flows as they are not subject to dividend distribution tax (under an InVIT). It’s worth keeping in mind the asymmetrical nature of the returns tradeoff between the upside for developer vs. discount for secondary buyer means even a small discount gets amplified into a much bigger returns upside for the primary developer.

Upside from an early exit will not be on offer for everybody; however, for the right projects there is a much more attractive return to be had as compared to what traditional develop and hold models indicate

While the above clearly substantiates the immense positive impact upfronting and recycling can have, not all primary developers will benefit from this. The end investors behind various vehicles (InvIT and otherwise) are going to be extremely picky about the offtaker — only central and perhaps a select few highly perceived state Discoms. Even with a solid offtaker in hand, the project SPVs themselves will have to be run in an impeccable manner from an O&M as well as financial perspective.

Furthermore, there are various implications in terms of structuring repayments for primary project loans as well. So while this upside will clearly not be on offer for everybody, it is certainly going to be there for the taking for those developers disciplined enough to run their project SPVs accordingly. And not capturing this aspect in a financial model ignores the true value these solar projects can generate, which after all, is the whole purpose of a financial model in the first place.

This article was originally published by the author on LinkedIn.

Lead image credit: depositphotos.com