You don’t have to be an ornithologist to know that birds are pretty good at flying. But while we know how they do it in general, the millimeter- and microsecond-level details are difficult to pin down. Researchers at Stanford are demystifying bird flight with a custom camera/projector setup, and hoping to eventually replicate its adaptability in unpredictable air currents.

“We really want to understand how birds are able to do the things that drones can’t,” explained graduate student Marc Deetjen, who designed the system, in a video from Stanford. “Specifically we want to know the exact shape of the wings as they fly.”

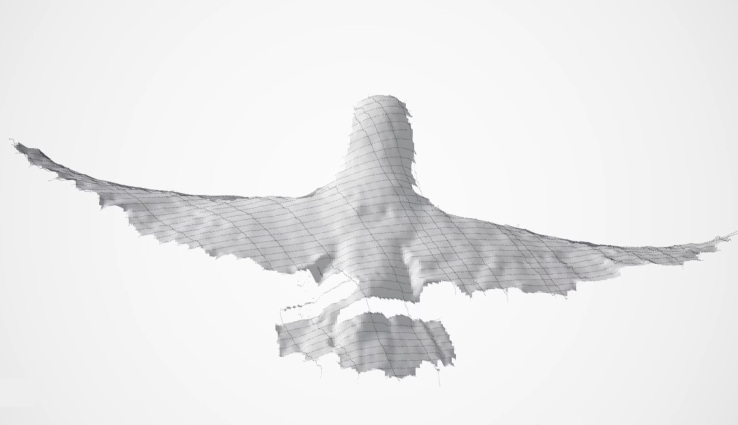

Deetjen and mechanical engineering professor David Lentink opted for a “patterned light” technique. A projector sprays out a grid of light with carefully engineered angles and spacing, and a high-speed camera picks up whatever that grid lands on. Depending on how those lines distort and move over time, the system can infer the exact shape of the object the pattern falls on.

In this case, of course, it’s a bird, specifically Gary, a 4-year-old “parrotlet.”

In this case, of course, it’s a bird, specifically Gary, a 4-year-old “parrotlet.”

“To make this work really well, we need to be able to see the light that’s projected on the wing,” said Deetjen. “That’s why we actually studied this with white birds — because they form a perfect flying projection screen.”

It works at short range and high speed, which isn’t always the case with other mapping tech like lidar and time-of-flight systems.

The results are not only useful but also eerily beautiful:

The very first tests of the system yielded interesting information: The bird’s angle of attack, an aerodynamic term for the angle at which air strikes the wing (or vice versa, depending on your frame of reference), was absurdly high. In an aircraft it would create so much drag that it would stall immediately and drop like a rock, or perhaps snap the wings off.

The very first tests of the system yielded interesting information: The bird’s angle of attack, an aerodynamic term for the angle at which air strikes the wing (or vice versa, depending on your frame of reference), was absurdly high. In an aircraft it would create so much drag that it would stall immediately and drop like a rock, or perhaps snap the wings off.

But Gary apparently was able not just to take off, but to convert this ridiculous angle into improved lift by redirecting the drag in an upwards direction. (I think.)

At any rate, the system is easy to deploy, accurate and could be used to track the minutest motions of other flying, hopping or stalking creatures. Future versions could use multiple cameras to form a more complete picture of the animal, but that’s a significantly harder problem.

For now the next step is to test the system in Stanford’s bird wind tunnel, which is something that exists.