Editors Notes: “In 40 years, historians will recognize that Sept. 4 was the day the petrodollar died. Here’s how you can protect your wealth before the petrodollar’s last day.”

By Jim Rickards

One of the most momentous wealth transfers in world history is happening in real time. Yet, it’s happening behind a veil of technical jargon, state secrecy, and hidden agendas that make it difficult for everyday investors to discern. Those who can under- stand this wealth transfer and use it to their advantage stand to make enormous gains. Today, we will prepare you to navigate the tumultuous markets that lie ahead.

This wealth transfer will be caused by the decline of the petrodollar and the rise of a new benchmark for pricing energy and wealth — which I will reveal today. The transition has already begun, but most analysts are ignoring it. On September 4, 2016, it will become too blatant to ignore.

The move away from the petrodollar is happening in part because the dollar is losing its status as the world reserve currency. However, those waiting for a single defining event when the dollar ceases to hold all value overnight will be disappointed. That’s not how currencies die. We’ve discussed the pound sterling’s displacement as a world currency at length in Intelligence Triggers — the process took three decades to play out, yet most investors didn’t realize what was happening until it was too late. By then, much of their wealth has been destroyed. The same thing will happen for many investors as the dollar fades.

The time to take action to preserve wealth and even to pro t is now. To do that, you’ll need to know the whole story and what it means for you. That’s the purpose of this special edition of Strategic Intelligence.

The Origin of the Petrodollar

The petrodollar story begins on October 6, 1973. Syria, Egypt, and other Arab nations launched a surprise attack on Israel on Judaism’s holiest day — Yom Kippur. Initially, Israel was on the defensive as Egyptian troops poured across the Suez Canal and the Syrians made inroads on the Golan Heights. Russia offered massive military aid to its Arab allies.

On the night of October 8, 1973, Israel went on full nuclear alert. Henry Kissinger, U.S. Secretary of State for just two weeks, was noticed of the Israeli threat to use nuclear weapons if its existence was threatened by the Arab invasion. On October 12, Kissinger and President Nixon ordered massive resupply of the Israelis through a strategic airlift.

President Anwar Sadat of Egypt had met secretly with King Faisal of Saudi Arabia on August 23, 1973 to negotiate the use of an “oil weapon” in the event of hostilities between Egypt and Israel. On October 16, 1973 the Arab oil weapon was deployed.

Saudi Arabia and other gulf nations raised the price of oil by 70% from $3.00 to $5.11 per barrel in retaliation for U.S. aid to Israel. This was the first in a rapid series of price increases. By December 12, 1973, oil was as high as $17.40 a barrel.

By October 25, 1973 the Yom Kippur War was over. Israel had emerged victorious. Israel not only repelled the Arab invaders, but it secured more territory than it held at the beginning of the war. But while the shooting war was over, the oil wars were just beginning.

The Arabs did not only increase the price of oil, they also reduced output and placed an embargo on exports to unfriendly nations. On November 5, 1973, Arab oil producers imposed a 25% production cut and threatened an additional 5% production cut, which was implemented on December 9.

The impact of these price increases, production cuts, and embargos on the U.S. economy was immediate and severe. The U.S. officially entered a recession in November 1973 and it lasted until March 1975. This was the most severe recession in the U.S. since the end of the Great Depression in 1940.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average took a sickening 36% plunge from October 31, 1973, just after the Yom Kippur War, to September 30, 1974. Eight years later, on September 30, 1982, the Dow Jones was still below the high reached just before the oil weapon was used. The 1970s were truly a “lost decade” for stocks because of the oil embargo and price increases unleashed by the Arabs.

In some ways, the die was cast even before the Yom Kippur War. On August 15, 1971, President Nixon ended the ability of U.S. trading partners to exchange dollars for gold at a fixed price. From 1971 to 1973, the dollar declined significantly in purchasing power measured both by U.S. price indices, and by the price of gold.

The Arabs were accustomed to a stable dollar and did not immediately know how to respond to the lost purchasing power of $3.00 per barrel oil. The Yom Kippur War was a catalyst, but it was also an excuse to do what they were struggling to do anyway — raise the dollar price of oil to compensate for the lost purchasing power of the dollar.

By the winter of 1974, America was desperate. The U.S. was experiencing recession and inaction at the same time, a condition later dubbed “stagnation.” Unemployment skyrocketed, citizens waited in long lines for scarce supplies of gasoline, the dollar was in free-fall, and America seemed held hostage to Arab kings and princes. The Arabs were seriously considering pricing oil in terms of ounces of gold to protect themselves against the decline of the dollar. Nixon was preoccupied with the Watergate scandal and calls for his impeachment. It was truly the winter of our discontent.

In the depths of economic recession and psychological depression, the petrodollar deal was invented. I was present at the creation. In February 1974, I was asked by the head of the American Foreign Policy Institute, Professor Robert W. Tucker of the Johns Hopkins School

of Advanced International Studies, to join him and four other foreign policy experts for a meeting at the White House with Dr. Helmut Sonnenfeldt, Kissinger’s deputy on the National Security Council. Sonnenfeldt was born in Germany like

Kissinger, and was a brilliant scholar of American foreign policy. His influence was mostly behind the scenes, but to insiders he was known as “Kissinger’s Kissinger.”

Tucker and I entered the White House complex around 6:00 pm through the security gate on Pennsylvania Avenue near West Executive Drive, closest to the West Wing. It was a cold night, but crisp with clear skies. Our small group were escorted to Sonnenfeldt’s office where we settled in for a strategy discussion.

Our main focus that night was a possible invasion of Saudi Arabia. The idea was to secure the oilfields, pump enough oil to supply western and Japanese needs, and price it at a level that would not be inflationary to avoid undermining confidence in the dollar. We debated the pros and cons of this plan, including possible supply disruptions and international reactions, until well into the evening. Then we said our goodbyes and went our separate ways.

The Arabs had imposed a voluntary price freeze on oil on January 7, 1974, and formally ended the oil embargo on March 17, 1974. They seemed to realize that the economic damage to the U.S. was so great that they might be pushing the U.S. to the brink of war; exactly the scenario we had discussed with Sonnenfeldt in the White House in February. Relations were still tense and the economic damage from the 1973 price hikes was ongoing. The temporary price freeze was not good enough. The U.S. needed a permanent solution to the threat posed by the Arab oil weapon.

In June 1974, President Nixon took advantage of the slight thaw in relations to meet with King Faisal in Saudi Arabia. This was an attempt to normalize relations after the strains of the Yom Kippur War and the oil price shocks of late 1973. It was also an effort to explore long lasting solutions to the dual problems of the oil weapon and the weak dollar.

President Richard M. Nixon meets with King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, June 1974

Separately from the invasion scenario, another plan for dealing with the Saudis was in the works. Kissinger and Sonnenfeldt were also the architects of this alternative plan, along with William E. Simon. At the time of my meeting with Sonnenfeldt, Simon was simultaneously Deputy Secretary of the Treasury and head of the Federal Energy Administration. On May 9, 1974, Simon was confirmed as Secretary of the Treasury.

In July 1974, Nixon sent Simon and his deputy, Gerry Parsky, on a secret mission to Saudi Arabia to work out the details of what became the petrodollar. Operating in close coordination with Kissinger and Sonnenfeldt, Simon spent four days in Jeddah, a city on Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coastline, meeting with Saudi counterparts.

The stakes could not have been higher. The future of the U.S. dollar, the health of the U.S. economy, and the replacement of U.S. influence with Soviet in uence in the Middle East were all at risk.

The Ultimate Win-Win

The deal that Simon offered was straightforward. The Saudis would agree to price oil in dollars, and to reinvest those dollars in U.S. Treasury securities and Eurodollar deposits in U.S. banks. In exchange, the U.S. would take steps to stabilize the exchange value of the dollar, and would agree to sell advanced weapons to the Kingdom. The new twist was that U.S. banks would “recycle” the petrodollars as loans to emerging markets in Latin America, South Asia and Africa. In turn, those countries would purchase U.S., European, and Japanese exports. That would reignite global growth and increase the demand for oil.

It was the ultimate win-win. The Saudis got weapons, safe investments, high oil prices, and increased demand for their oil. The U.S. got debt financing, weapons sales, increased Middle-East influence, and a dominant role for the dollar in international reserve positions. Once oil was priced in dollars, every country in the world would need dollars because every country in the world needed oil.

The principal architects of the Petrodollar System: from left to right, William E. Simon, “Energy Czar” and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury; Helmut Sonnenfeldt, National Security Council Senior Staff; and Henry A. Kissinger, National Security Advisor, and U.S. Secretary of State. I met with Dr. Sonnenfeldt in the White House in February 1974 to strategize on a policy response to the Arab oil embargo. The embargo gave rise to the petrodollar.

The principal architects of the Petrodollar System: from left to right, William E. Simon, “Energy Czar” and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury; Helmut Sonnenfeldt, National Security Council Senior Staff; and Henry A. Kissinger, National Security Advisor, and U.S. Secretary of State. I met with Dr. Sonnenfeldt in the White House in February 1974 to strategize on a policy response to the Arab oil embargo. The embargo gave rise to the petrodollar.

The Nixon-Simon-Kissinger petrodollar deal was brilliant. Yet, there were several problems in the implementation. The Saudis are notorious for delay in decision making. They did not want to commit to the deal right away. They wanted time to consider alternatives including gold. The Saudis also wanted guarantees of secrecy. They did not want the world to know about their purchases of U.S. Treasury securities.

Nixon resigned in August 1974 because of Watergate and Gerald Ford became president. Ford kept Kissinger, Simon, and Sonnenfeldt in office, but the transition gave the Saudis another excuse for delay as the new president found his footing.

The petrodollar negotiations dragged on for months, and so did the U.S. recession. By late 1974, Kissinger needed to send a message to the Saudis. It was time to play rough.

On January 1, 1975, Commentary magazine published one of the most famous articles in the history of American foreign policy. It was written by Robert W. Tucker, the same man who had introduced me to Sonnenfeldt. The title of the article was, Oil: The Issue of American Intervention. In effect, the article revived the invasion scenario that Tucker, Sonnenfeldt and I had discussed in the White House the year before.

Tucker did not pull any punches with regard to the threat of invasion. Here’s an extended excerpt from Tucker’s land- mark article:

“…Until as recently as the middle 1960’s, what the instances of armed intervention demonstrate is that great powers continued to manifest a willingness to use force against small states to vindicate interests which affected their well-being less than it is likely to be affected by a continuation of the policies pursued today by the major OPEC countries.”

Once Tucker had established a precedent for military intervention based on prior armed interventions by major powers against weaker ones where vital interests where threatened, he went on to give a detailed battle plan with precise geographical coordinates:

“[The] feasibility of [military] intervention depends upon whether there is a relatively restricted area which, if effectively controlled, contains a sufficient portion of present world oil production and proven reserves… to break the present price structure by breaking the core of the cartel politically and economically. The one area that would appear to satisfy these requirements extends from Kuwait down along the coastal region of Saudi Arabia to Qatar. It is this mostly shallow coastal strip less than 400 miles in length that provides 40 per cent of present OPEC production and that has by far the world’s largest proven reserves…”

Tucker next addressed one of the principal objections to armed intervention: that Saudi Arabia would destroy the infrastructure before the U.S. could effectively seize it. This would give the U.S. a Pyrrhic victory and cause severe oil shortages, at least in the short-run. Tucker argued that such behavior on the part of Saudi Arabia was unlikely and against their interests:

“Intervention would prove self-defeating, the argument runs, if only because we would inherit a shambles that might well take eight or nine months to repair. Is the assumption of systematic destruction from the wells to the terminal areas a realistic one?… The kind and scope of the destruction commonly envisaged evokes the thoroughness of the destruction wrought by German forces during World War II as they withdrew from the East. Would the Arabs match this record? There is little in their past behavior to suppose that they would.”

Tucker demolished these concerns about infrastructure damage by arguing that even if the Saudis attempted to destroy their infrastructure, the impact would be limited and the disruption would last no longer than three to four months. He suggested that Western nations build up a strategic oil reserve of 60-90 days’ supply so they could ride out any temporary disruption from a destruction of oil infrastructure.

Finally, Tucker administered the coup de grâce to any illusions that Saudi Arabia could use oil as a weapon: Even if Saudi Arabia would extort dollars from the U.S with exorbitantly high oil prices, the Saudis will have no choice but to invest those dollars in U.S. dollar-denominated instruments. This could include Treasury bills, bank Eurodollar deposits, or other U.S. assets. In any event, the U.S. could default on its obligations or expropriate the assets. In effect, the Saudis were “hostage” to the dollar system whether they liked it or not.

The message was clear, and the threat was unmistakable. Either the Saudis would and a way to cooperate with the U.S., or the U.S. would destroy them militarily, financially, or both.

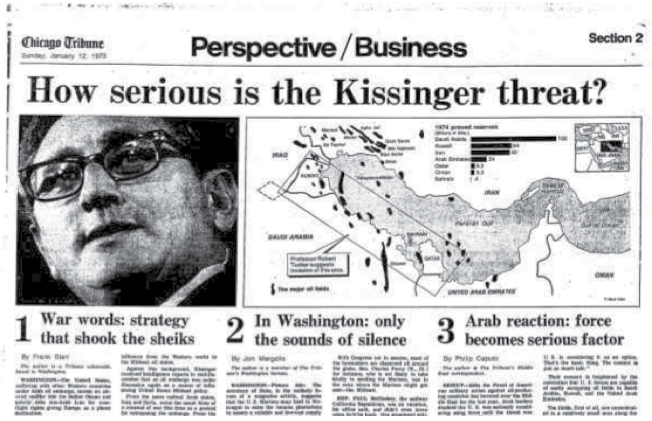

The impact of the Tucker article was widespread and immediate (Click here to read the entire article). Just days after Tucker’s article appeared, the Chicago Tribune article refers specially to the invasion area described by Tucker and shows it on a map. More to the point, the headline of the article does not refer to the threat as coming from Tucker, but rather as “the Kissinger threat.”

The Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1975. The caption pointing to the box on the Gulf map says, “Professor Robert Tucker suggests invasion of this area.” Robert Tucker was my introduction to Helmut Sonnenfeldt and was with me in the White House when we first discussed the invasion plans with Sonnenfeldt one year earlier.

The Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1975. The caption pointing to the box on the Gulf map says, “Professor Robert Tucker suggests invasion of this area.” Robert Tucker was my introduction to Helmut Sonnenfeldt and was with me in the White House when we first discussed the invasion plans with Sonnenfeldt one year earlier.

Reference to the Kissinger Threat led to speculation that while, the article may have been written by Robert W Tucker, it was done so at the behest of Henry Kissinger. It would have been too politically provocative and damaging to have the threat issued by Kissinger directly. Tucker was a convenient stalking horse and Kissinger could say the article was just some musing by an academic, and did not reflect U.S. intentions. Kissinger had played his trump card and left no fingerprints.

Once the U.S. laid its invasion cards on the table, the Saudis swiftly finalized the negotiations on the petrodollar deal. The major concession the Saudis received was an agreement by the U.S. not to disclose the exact size of Saudi investments in U.S. Treasury securities. This secrecy was maintained for over forty years, until May 2016, when the Treasury finally revealed that size of Saudi holdings of U.S. Treasuries. (However, even the new of official figure is misleading because it ignores Treasury securities owned by Saudi Arabia but held by offshore intermediaries in the Cayman Islands and other offshore banking centers).

In addition, Tucker’s suggestion for an oil reserve became the basis for the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which was signed into law by President Gerald Ford on December 22, 1975, less than one year after Tucker’s article appeared. This reserve not only protected the U.S. against supply and infrastructure disruptions, it also allowed the U.S. to sup- port oil prices by purchasing oil even in times of reduced demand, which would maintain Saudi revenues under the petrodollar deal.

By early 1975, not long after the Tucker invasion threat article was published, the petrodollar deal was in effect. The stock market had begun its recovery earlier in September 1974. The U.S. recession officially ended in March 1975. The weapons sales to Saudi Arabia started immediately. All that remained was for the U.S. to hold up its end of the deal by maintaining a stable value for the dollar.

The Beginning of the End

Initially the petrodollar deal worked well. In the 5 months after the deal was finalized, the dollar rallied 4.6%. The dollar declined only slightly through the end of 1976, but then began a precipitous decline in 1977.

It was in late 1977 that I joined Citibank as a senior officer in their international division. From there I had a front row seat to see how Citibank, then the largest bank in the U.S., handled its end of the petrodollar deal. They recycled Saudi Eurodollar deposits to emerging markets borrowers in Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and elsewhere. This petrodollar recycling was led by, legendary Citibank CEO, Walter Wriston, and his counterpart CEO at Chase Manhattan Bank, David Rockefeller.

By October 1978, the dollar index had fallen nearly 13% from the 1975 high. The Saudis saw this rapid decline of the dollar as a breach of the petrodollar deal. They retaliated by doubling the price of oil between April 1979 and April 1980.

Once again, the U.S. economy dipped into recession and Americans waited in long lines to get gasoline. It seemed that the petrodollar deal was coming apart at the seams after only four years. By now, Jimmy Carter was president and Kissinger, Simon, and Sonnenfeldt had all left government to purse private careers.

Still, the petrodollar deal was too important to both the Saudis and the U.S. to fall by the wayside. President Carter saved the day by appointing Paul Volcker as Chairman of the Federal Reserve in August 1979. Volcker immediately set out to save the dollar by raising interest rates from 11% when he took office to a high of 19% in 1981.

It was tough medicine for the U.S. economy, but it worked. Inflation plunged from 15% in 1980 to 4% by the end of 1982. The Fed’s dollar index soared from 84.13 in October 1978 to 92.48 in November 1980, about where it was when the petrodollar deal began.

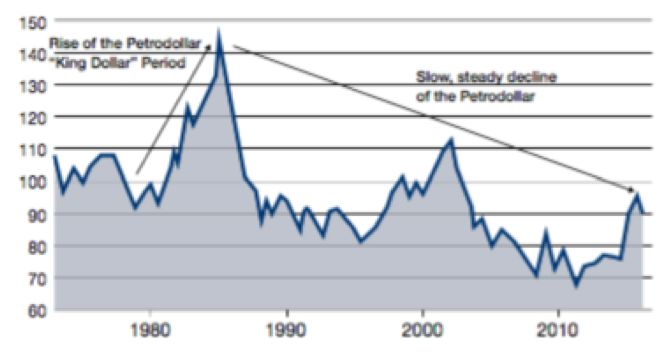

What happened next secured the success of the petrodollar deal for the next thirty years. Volcker’s tight money policy combined with Ronald Reagan’s low taxes and reduced regulation sent the U.S. economy and the U.S. dollar on a tear. By March 1985, the dollar index reached an all-time high of 128.44, a spectacular 53% gain from the October 1978 low.

This period of the 1980s was the heyday of “King Dollar.” The Saudis were pleased that the purchasing power of their dollars was restored and enhanced. The U.S. benefited from low inflation, strong growth and ample oil supplies. This spectacular rise in the dollar from the 1978 low to the 1985 high is shown in the chart below. [Editor’s note — index numbers on the chart below are different from those used above because the chart covers major currencies only, while the Fed’s broad index covers all trading partners. However, the trend and direction of dollar index movements are substantially the same by both measures]:

From the 1985 dollar index high, the dollar was forced lower as a result of the Plaza Accord in 1985. Still, the petrodollar deal was not seriously threatened and the dollar was stabilized beginning in 1987 as a result of the Louvre Accord.

From the 1985 dollar index high, the dollar was forced lower as a result of the Plaza Accord in 1985. Still, the petrodollar deal was not seriously threatened and the dollar was stabilized beginning in 1987 as a result of the Louvre Accord.

Both Republican and Democratic administrations under Reagan, Bush 41, Clinton, and Bush 43 were committed to the mantra of a “strong dollar.” For 35 years, from 1975 to 2010, the petrodollar deal remained intact despite some oil price increases and dollar volatility along the way. The dollar solidified its role as the leading reserve currency and the leading payments currency by far.

But by 2009, a new economic crisis had planted the seeds for the end of the petrodollar deal. Global growth and trade collapsed in the panic of 2008. The world was mired in a severe recession, worse than the one in 1973–1975 that prompted the petrodollar deal, and the worst since the Great Depression.

In September 2009, world leaders gathered in Pittsburgh for the G20 Leaders’ Summit. President Obama and his chief international economic advisor, Michael Froman, proposed a plan to reignite world growth. The plan was for each major economic group to move away from a sec- tor it had over-relied on and toward a sector that offered growth potential. For China and Japan, this meant moving from capital investment to consumption. For Europe, this meant moving from exports to investment. The U.S. part of the global re-balancing deal was to increase exports.

President Obama and his Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economic Affairs, Michael Froman, were the principal architects of the new currency war in January 2010, which marked the beginning of the end for the petrodollar.

President Obama and his Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economic Affairs, Michael Froman, were the principal architects of the new currency war in January 2010, which marked the beginning of the end for the petrodollar.

President Obama’s officially declared this goal on January 27, 2010, in his State of the Union Address:

“…the more products we make and sell to other countries, the more jobs we support right here in America. So tonight, we set a new goal: We will double our exports over the next several years, an increase that will support two million jobs in America.” (emphasis added)

Doubling exports to increase jobs and growth was certainly a laudable goal. There’s only one problem. The U.S. could not double the labor force or double productivity. The only way to double exports was to improve the terms of trade by cheapening the U.S. dollar.

Obama’s speech was an official declaration of a new currency war. By July 2011, just 18 months after the address, the dollar index stood at 80.48, an 8% decline and a new all-time low.

The difference in 2011 was that this was not a case of the world trashing the dollar against the wishes of the U.S. This time, the U.S. was trashing the dollar itself as a matter of policy. Now, the U.S. was saying a cheap dollar was more important than promises to trading partners; exactly what Richard Nixon said in effect when he went off the gold standard in 1971.

The U.S. had turned its back on the petrodollar deal. All that remained was to see the Saudi and the global responses to the new currency war.

New World Money: the Petro-SDR

The response to U.S. efforts to cheapen the dollar in 2010 — 2011 was not long in coming. It came from four directions — IMF, Russia, China, and Saudi Arabia. (Byron and Nomi will be discussing Russia and China today, respectively.)

Less than a year after Obama’s declaration of a new currency war, the IMF released a paper that is a blueprint for implementation of a new global reserve currency called the Special Drawing Right, or SDR.

On December 1, 2015, the IMF announced that the Chinese Yuan would be included in the basket of currencies used to determine the value of one SDR. With China on board, the SDR is poised to become the defacto global reserve currency.

China’s and Russia’s immediate response to the coming dollar collapse and rise of the SDR is to buy gold. (It’s not yet possible to diversify heavily into SDR denominated assets because there are very few SDR assets available.) Russia has acquired over 1,000 tons of gold in the past seven years, and China has acquired over 3,000 tons of gold in the same time. Combined Russian and Chinese gold purchases are over 10% of all the official gold in the world. China has also acquired billions of SDRs in secret secondary market transactions brokered by the IMF.

Saudi Arabia’s response has been more subtle, but may be more dramatic in the end. Relations between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. have deteriorated sharply over the course of the Obama administration. The primary cause was the Iran-U.S. nuclear negotiations and what amounts to the U.S. recognizing Iran as the leading regional power.

In the past few months, the U.S. ended the secrecy surrounding Saudi ownership of U.S. Treasury securities (in place since 1975). The U.S. also released a formerly top secret 28-page section of the 9/11 Commission Report that clearly reveals links between members of the Saudi royal family and the 9/11 hijackers and Al Qaeda. The Saudis have threatened to dump their U.S. Treasury securities in response to the release of the secret report, but so far that threat has not materialized.

Saudi Arabia is dealing from a position of weakness in relation to the U.S. Saudi Arabia is now running a fiscal deficit rather than a surplus, so the issue of where to invest reserves is moot. In fact, Saudi has been selling its reserves, mainly U.S. Treasuries, to cover its fiscal deficit.

The U.S. is no longer dependent on Saudi Arabia for energy supplies. It has become a net exporter of energy and has the largest oil reserves in the world. All of the conditions that gave rise to the petrodollar now stand in the exact opposite position of where they were in 1975.

Neither the U.S. nor Saudi Arabia have much leverage over the other, in contrast to 1975 when each side held powerful trump cards. This does not mean that oil will be priced in a currency other than dollars tomorrow. It does mean that a new pricing mechanism is possible and no one should be surprised if it happens.

Saudi Arabia could easily price oil in Yuan, then swap the Yuan for Swiss francs or SDRs, and use the proceeds to add to its reserves or buy gold. Saudi Arabia could also price oil in SDRs or gold and hold those assets or swap them for other hard currencies to diversify away from dollars. The possibilities are numerous. The conversion of oil prices away from dollars to some alternative is just a matter of time.

All of these trends — IMF support for SDRs, Russian and Chinese support for gold, and Saudi Arabia’s search for a new benchmark for oil — will come to a head on September 4, in Hangzhou, China at the G20 Leaders’ Summit, almost seven years to the day after the Pittsburgh G20 Summit that spawned the new currency war. China’s President Xi is the President of the G20 for 2016, and will stride on the world stage as an equal partner with the U.S. in the management of the international monetary system.

September 4, 2016 will be the day the dollar died, “not with a bang but with a whimper” in the words of T. S. Eliot.

Less than four weeks after the G20 Summit, the Yuan will officially join the SDR. The Yuan will make up over 10% of the SDR. From there, new issuance of SDRs will be supported by China because every time the IMF issues new SDRs, they will be expanding the role of the Chinese Yuan as a reserve currency.

Gold, Yuan, and SDRs all have one thing in common — they are alternatives to the dollar. As momentum toward these alternatives grows, the role of dollars as a reserve currency could diminish quite quickly — like sterling’s role between 1914 and 1944. The result for dollar holders will be exactly the same as the result for sterling holders: inflation and lost wealth. New political and financial arrangements, and new forms of energy, will no doubt emerge over time (as Nomi explains in her article).

The key to wealth preservation is to move out of the declining form of money — dollars — and into the rising forms of money — gold and SDRs — sooner rather than later.

Editor Notes: Something newer then the author of this article is aware of called .G coin from Dao Gold the only private blockchain gold backed digital currency designed for long term purchasing power with built in stability programing that looks over the horizon 100 years using the latest AI technology to guide the way.