Most people might not remember that websites once had icons that said, “This site has been optimized for Internet Explorer,” but, two decades ago, it wasn’t uncommon.

Just like today’s battle between Web 2.0 monopolies and Web 3.0 communities, at the beginning of the early consumer internet, there was a similar battle waged over who would own the portal to it: A closed-source global monopoly, or an open-source nonprofit.

A battle for the soul of the internet

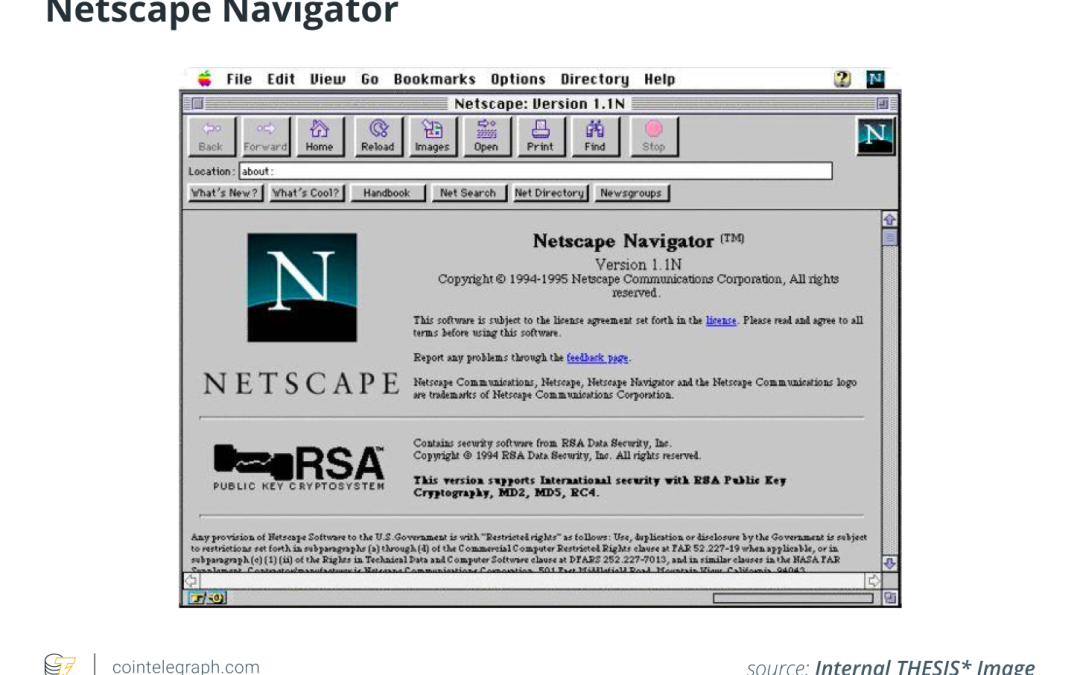

Long before Web 3.0, the browser wars defined the early internet. Netscape Navigator was the first consumer browser in the market and the browser of choice for the first users of the web. For many, it was synonymous with the dawn of the internet.

Slowly but surely, however, Microsoft leveraged its monopoly position in the OS space to push its closed-source alternative:Internet Explorer (IE). It was able to outcompete Netscape and become the default choice for users simply by packaging the browser with Windows.

In 1998, Netscape open-sourced its browser and helped create the Mozilla Foundation that supported a free software community made up of its contributors. By 2002, the Mozilla Firefox browser, based on open-source principles, launched under the initial codename ”Phoenix,” in reference to how it rose from the ashes.

A battle ensued for the soul of the internet. Internet Explorer was closed-source; Firefox was open-source. Internet Explorer was launched by a monopoly; Firefox was run by a foundation.

Firefox broke Microsoft’s closed-source stranglehold, paving the way for Chrome, which was built on the open-source Chromium project. Together with the rise of the mobile web, it threw a wrench into Internet Explorer’s gears. If it hadn’t, users might still be seeing “This site has been optimized for Internet Explorer” when they loaded this page.

Internet Explorer was also at the heart of Microsoft’s monopoly case, which resulted in Microsoft’s 10-year reinvention of itself as a champion for open-source software.

A new internet

Flash forward to today. Web 3.0-enabled wallets are the tools that millions are using to participate in the brave new world of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), community-driven DeFi protocols and the Metaverse. They are the portal to these applications, just like the browser was the portal to the websites of the early internet. Soon they will be the default interface for a new internet — the land they will be fighting for.

Related: The three traits of Web 3.0 that fix what went wrong with today’s internet

The more things change

Once again, we have a monopoly that’s getting in the way. It’s not free and open-source. Sites are optimizing for it. We have to fight for this again. Much like IE’s role in shaping Web 2.0, many DApps and Web 3.0 applications have started to optimize for MetaMask, the current market leader in digital wallets. While it is true that users will follow the path of least resistance, this could have the adverse effect of putting the entry-point to the ecosystem in the hands of a conglomerate.

Just like IE, MetaMask has started to bank on monopolistic practices and a walled-garden approach that harkens back to Web 2.0 and its regressive business models. After switching its codebase to a tiered proprietary license, it went from around 500,000 to over 21 million monthly active users in little more than a year as the mainstream flocked to Web 3.0. These same users paid over $237 million in service fees on its in-wallet swaps feature during this timeframe.

Based on these numbers, the project raised $200 million in capital from a wide range of firms, including HSBC. This was all good for ConsenSys, the conglomerate that owns MetaMask’s codebase. However, none of it had any benefit for its users. Adding to that, former employees and shareholders are now sounding the alarm about ConsenSys’ involvement with Wall Street firms such as JPMorgan — a relationship that is at odds with its initial ideas about the openness and decentralization of finance.

Many have felt that this growing market penetration and MetaMask’s Web 2.0 approach to the development of digital wallets betrays the potential of the Web 3.0 stack. Decentralized applications have opened opportunities for participatory business models that are perhaps lost on the same initial proponents of a more open internet. Business models that can redefine the relationship between tools and their users.

Related: The three traits of Web 3.0 that fix what went wrong with today’s internet

But they don’t have to stay the same

History doesn’t have to repeat itself. In this new context, we’ll see plenty of historical echoes when it comes to Web 3.0 and digital wallets. There will continue to be closed-source, monopoly-run software, and there will be new kinds of open-source and community-run alternatives. However, unlike Web 2.0, users now have a bigger say in deciding where things will go. They now have the choice of building, governing and participating in the benefits of open-source software that they can actually own.

Web 3.0 is creating an environment where the copyright-heavy, walled-garden, profit-driven business models of Web 2.0 won’t work as well as they did in the past. The projects that are being developed on this stack are open-source, composable and community-driven. When we’re talking about technologies that enable programmable money, these details make all the difference.

Related: Is a new decentralized internet, or Web 3.0, possible?

The nature of Web 3.0 has made it possible for any project to fork the codebase of any other project and develop a better alternative — a situation that ultimately benefits users. At the same time, having decentralized access to capital and community incentives makes any project capable of market penetration.

This flips the centralized Web 2.0 model on its head and makes community the make-or-break factor in any Web 3.0 project. Some examples of this are seen in the current DeFi 2.0 trend towards protocol-owned liquidity and the increasing purchasing power of DAOs. Sadly, the interface where many users access these applications is still stuck in Web 2.0.

What to expect

A growing number of users are becoming familiar with the possibilities of Web 3.0. Going forward, they will expect the interface they use to access these applications to provide them with the same benefits as the applications themselves. It might be too early to tell which current project will share the fate of Internet Explorer. It’s not too early to know that Web 3.0 users will want to own a piece of the software they trust with their digital assets.

This article does not contain investment advice or recommendations. Every investment and trading move involves risk, and readers should conduct their own research when making a decision.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.