Earlier this year, Joshua Browder, CEO of AI startup DoNotPay, attempted to bring a robot lawyer into a California courtroom, despite almost certainly knowing that it was illegal in almost all 50 states to bring automated assistance like this into a courtroom.

DoNotPay bills itself as the “world’s first robot lawyer” whose goal is to “level the playing field and make legal information and self-help accessible to everyone.” It helps to serve society’s lower-income segment to lower medical bills, appeal bank fees, and dispute credit reports. It claims to have helped more than 160,000 people successfully contest parking tickets in London and New York.

It was denied entry to the California courthouse, however, because “under current rules in every state except Utah, nobody except a bar-licensed lawyer is allowed to give any kind of legal help,” Gillian Hadfield, professor of law and director of the Schwartz Reisman Institute for Technology and Society at the University of Toronto, tells Magazine.

Still, in the age of ChatGPT and other stunning artificial intelligence devices, Browder’s attempt could be a foretaste of the future.

“The DoNotPay effort is a sign of what is to come,” Andrew Perlman, dean and professor of law at Suffolk University Law School, tells Magazine. “Certain legal services, including many routine legal matters, can and will be delivered through automated tools. In fact, it is already happening at the consumer level in numerous ways, such as via LegalZoom.”

Such help is urgently needed in the view of many. In the U.S., low-income Americans “do not receive any or enough legal help for 92% of their civil legal problems,” according to a Legal Services Corporation study (2022). Almost half surveyed don’t seek help because of high legal costs, and more than half (53%) “doubt their ability to find a lawyer they could afford if they needed one,” according to the LSC survey.

“This access-to-justice gap is a serious problem, and automated tools can be an important part of the solution,” comments Perlman.

Can AI democratize legal services?

It may only be a matter of time before AI reaches the courtroom. If so, it could help to wring human bias out of the legal system. “In a legal setting, AI will usher in a new, fairer form of digital justice whereby human emotion, bias and error will become a thing of the past,” says British AI expert Terence Mauri, author and founder of the Hack Future Lab.

Will it advance the day when legal services are truly democratized? “Absolutely,” says Hadfield. “This is the most exciting thing about AI now.” Not only can it reduce the cost of legal services in the corporate sector — “and I think that’s coming — “but the huge payoff will be in addressing the complete crisis we face in access to justice.”

But more work may still be needed before AI becomes common in the courthouse. The law does not have much tolerance for technical errors. The stakes are simply too high. “I’ve used ChatGPT, and it often summarizes the law correctly. But sometimes, it makes mistakes,” John McGinnis, a law professor at Northwestern University told USA Today. “And (that’s) not a surprise. It’ll get better. But at the moment, I think going into the courtroom was something of a bridge too far.”

Hadfield herself has been working in Utah and elsewhere to establish regimes for licensing providers other than lawyers to provide some legal services. Consumer access to legal services is necessary for the interests of fairness and is increasingly doable, given the rapid evolution of technology. As Hadfield explains to Magazine:

“I don’t think a fully unregulated/unvetted DoNotPay should be out there, but there should be an easy way to license it against the standard: ‘Does this make the user better off than they are now?’”

Most people engaging with the law today — including the people DoNotPay is aiming to help — “get zero legal assistance, so that bar may not be high,” adds Hadfield.

A global need

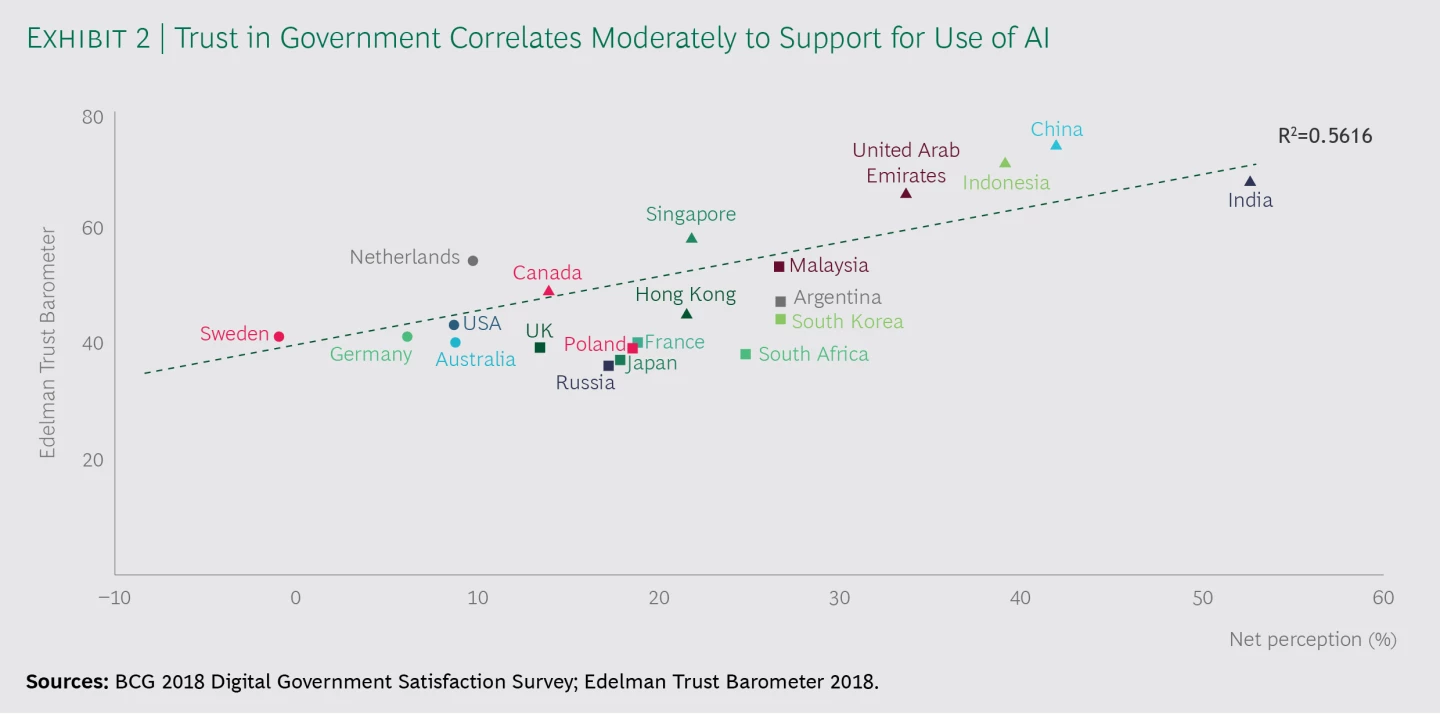

AI’s promise of delivering accessible, reasonably priced legal services could soon gain traction beyond the United States, too. Indeed, AI-driven solutions may be even more welcome in the developing world. A Boston Consulting Group study on “The Use of AI in Government,” for example, found that people in less developed economies “where perceived levels of corruption are higher also tended to be more supportive of the use of AI.” Those surveyed in India, China and Indonesia indicated the strongest support for government applications of AI, while those in Switzerland, Estonia and Austria offered the weakest support.

“Basic services such as drafting wills or simple contracts, or challenging government decisions, should not require the services of a lawyer,” Simon Chesterman, a David Marshall professor and vice provost at the National University of Singapore, tells Magazine, acknowledging that “the emergence of chatbot lawyers offers some short-term gains in terms of access to justice.”

More sophisticated legal questions will continue to require human lawyers and judges for the foreseeable future, however, Chesterman adds. Indeed, the BCG survey found that the majority of those surveyed globally “did not support AI for sensitive decisions associated with the justice system, such as parole board and sentencing recommendations.”

Sell or hodl? How to prepare for the end of the bull run, Part 2

William Shatner Tokenizes his Favorite Memories on the WAX Blockchain

A role for blockchain?

Is there a place for blockchain technology when it comes to bringing legal services to the under-served — perhaps working in tandem with artificial intelligence? Some think so. A legal system is built on a foundation of trust. People must believe that decisions are made in accordance with principles of fairness. This is where black-box AI solutions like ChatGPT can come up short. One can’t easily see how decisions are being made.

Public blockchains, by contrast, are famously transparent. They provide a clear, tamper-free ledger of transactions or interactions from a project’s beginning. “It is evident that the deployment of digital technologies, such as blockchain, is key to the development of AI,” writes Antonio Merchán Murillo, a professor at Spain’s Pablo Olavide University.

Blockchain’s strengths — transparency, traceability, decentralization and authentication — can complement AI, whose opaque algorithms can often confound. “Blockchain has the mission of generating trust, transparency, and acting as a mediator,” explains Murillo, and it can enable AI projects “to act and connect with each other” as well as provide “valuable information about origin and history.”

Smart contracts in particular could play a role in an evolving legal system. “In the near future, many commercial contracts will be written as smart contracts,” Joseph Raczynski, a futurist and technology consultant, tells Magazine. Both technologies will be transformative for the law, he says:

“Unquestionably, the legal industry is primed to be significantly impacted by both AI and blockchain in the not-too-distant future.”

Smart contracts are really just snippets of computer code, however, so it bears asking: Are they enforceable? Perhaps. It depends on the jurisdiction. In the U.S., “smart contracts are a type of contract, and therefore they’re enforced like all contracts in state and federal court systems,” attorney Isaac Marcushamer told LegalZoom. One drawback is that smart contracts can’t easily be changed, and at present, they are used mainly for simple transactions. As the technology evolves, however, many think they will perform more complex tasks.

Recent years have seen a proliferation of decentralized justice systems. Prominent among them is Kleros, “a decentralized blockchain-based arbitration solution that relies on smart contracts and crowdsourced jurors,” according to a recent law journal article. Kleros is mainly used in business contract disputes — e.g., “car insurer did not pay for the repair” or “the airline did not reimburse the canceled flight.” When a dispute arises, “Kleros selects a panel of jurors and sends back a decision.” According to Kleros’ white paper, it relies on “game theoretic incentives to have jurors rule cases correctly.”

Importantly, Kleros doesn’t charge user fees. It makes money indirectly through the appreciation of its PNK tokens that are needed to access the platform. In this way, its “decentralized sheriff contributes to the public good by filling a regulatory hole with respect to the crypto market,” according to the law journal article. The platform faces major obstacles before it can go mainstream, however, among them finding regulatory acceptance, the authors add.

A risk-averse industry

Overall, legal systems will not be disrupted immediately. “Despite the fact that AI has hit an inflection point recently, it’s unlikely that we will see AI assistance directly interacting in the next year,” predicts Raczynski. “However, in the next two or three years, I think it is highly possible select jurisdictions will test it.”

The reason is that lawyers and the legal industry generally tend to be “extraordinarily risk averse,” Raczynski adds. “The idea that AI will act as a lawyer in the courtroom imminently is doubtful.”

Michael Livermore, a professor at the University of Virginia’s School of Law, stated last year that a computer-written legal opinion is at least 10 years away. Asked if more recent advances in natural language processing (NLP) and other forms of AI had changed his timetable, Livermore tells Magazine:

“There is no doubt that current NLP is quite impressive, and it’s easy to foresee a tool coming online soon that could write a pseudo-legal opinion — i.e., a document that’s written in the style of a legal opinion. But writing a convincing and sustained argument, that is grounded in a reasonable interpretation of existing law — I think we’ll still have to wait a few years for that.”

It is hard to predict how “the involvement of robot lawyers may shape the dynamics of trial hearings and other judicial proceedings,” Zhiyu Li, an assistant professor in law and policy at Durham University, tells Magazine, “for example, whether and how litigants can communicate with their robot lawyers during the trial.”

Also, what if robot lawyers are suddenly sidelined by technical difficulties? More procedural rules may be needed to ensure the rights of litigants assisted by machines during proceedings, says Li. “For the time being, I have reservations about AI’s readiness to function like a human lawyer in trials,” she adds.

“Lives are at stake”

Another concern: Do the developers of legal bots have sufficient knowledge and experience of the law? Is the data that they are using to “train” their algorithms relevant and up to date? Will they inadvertently omit data that “could cause key evidence or elements to be filtered out or overlooked by a robot judge or AI software?” asks Li. “The decision-making of criminal cases deserves so much attention because oftentimes criminal defendants’ freedom and even their lives are at stake.”

Others draw a line between lawyers using AI to conduct research and robo-judges rendering decisions in criminal cases. Replacing human judges entails a serious raising of the AI ante.

“There is something critical about being judged by another human,” says Hadfield. “On the other hand, vast numbers of people [already] get no or very little human judgement in their cases — think small claims courts where 50 cases can be decided in a day.”

Human judges supportedby technology could represent a sensible middle ground. AI algorithms could be used to ensure bias (racial, gender, age, etc.) isn’t occurring. This could “reassure everyone that they are getting fair, neutral, accurate and unbiased judgement,” says Hadfield.

Using AI to strategize

AI will play a significant role in the preparation work that litigators engage in behind the scenes today “in their research and, increasingly, strategy,” says Raczynski. “Legal outcomes can now be empirically weighed via prediction models using similar, previously litigated cases, and their docket information by judge and jurisdiction.” Judges exhibit patterns that can be revealed by machine learning algorithms, and attorneys may increasingly use AI to discern those patterns.

Does all this portend an upending of the world’s legal systems? Are lawyers an endangered species?

“As basic legal services are outsourced to machines, the demand for junior lawyers will diminish,” said Chesterman. “That raises the question of how we will find the next generation of senior lawyers if they can’t cut their teeth as juniors.” Moreover, in many jurisdictions, this is leading to a broadening of the scope of work for lawyers — as well as the emergence of allied legal professionals — to support the industry, he adds.

AI search, workflow and automation tools combined with NLP and natural language generation models “will vastly reduce the need for routine lawyerly work,” says Raczynski, while in litigation, “it is conceivable that a Kleros — decentralized alternative dispute resolution system — could be a model to resolve conflict rather than leveraging the courts.”

“I think we are about to see major disruption in our legal systems,” adds Hadfield.

Still, “even with significant automation, lawyers will play an essential role in society and the delivery of legal services,” predicts Perlman. “AI does not mean the end of lawyers, but it might mean the end of legal services as we know it.”

“Large law firms will survive by handling highly complex issues,” says Raczynski. Small and medium-sized firms may not fare so well. “Across the industry, it’s the cookie-cutter work that most firms do now that will implode.”

AI for capital cases

But surely not all legal decisions can be entrusted to algorithms? What about capital cases where an individual is charged with first-degree murder? Can one really depend on an algorithm when a human life is on the line?

“In the early phases of any technology, especially in the legal industry, mistakes are not acceptable,” Raczynski tells Magazine. Still, “I firmly believe, in 15–20 years, we will trust algorithms to adjudicate the most complex legal cases.” At that time, many more contracts will rely on code and increasingly become more universal. Code will be more trustworthy, defined and clear.

The digital database of legal cases that permit algorithms to “learn” will also be vast, Raczynski adds. “At the very least, these algorithms will be a sort of augmented intelligence for judges to help them make a decision.”

Thus, the legal community will probably begin by applying AI to less significant use cases, such as contesting parking tickets. More consequential AI-aided cases will come later, probably after some kind of track record has been established.

And all this still doesn’t mean that all legal services should be delivered in an automated way, either — as with the aforementioned capital cases. “We will need to harness these new tools in ways that give the public greater access to legal services while ensuring appropriate protections for the legal system and society,” says Perlman.

One will also need to remember “that law is a social and political process, not just a set of fancy calculations,” adds Livermore.

Are blockchain-based legal agreements coming?

Smart contracts hosted on blockchains might in the future streamline traditional lawyers’ work product, reducing billing hours. Futurist Joseph Raczynski illustrates for Magazine how a smart contract with its conditional — i.e., if/then — statements can be used to create a trust for estate planning.

This (fictitious) trust stipulates the transfer of an estate’s assets upon certain conditions: First, both parents must be dead. Second, the two children — the beneficiaries — must be married in order for them to split the estate equally. “If one child is married and the other is not, the child that is married gets the entire estate,” Raczynski explains.

The trust is written as a smart contract saved on a blockchain with code that identifies parameters that are contingencies or possibly subject to change. “Saved as a smart contract on a blockchain, it is now in an immutable state but has actionable items embedded in it. The only people that have access to this document are the attorney that drew it up and her client.”

The smart contract is checked regularly by a trusted source — i.e., an “oracle” — to determine if both parents are still alive, explains Raczynski. “One day, the computer identifies that the parents have passed.” It now has to determine the marital status of both children:

“Through another API computer call to that oracle, it finds out that one child is married, and the other child is not, and subsequently sends 100% of the liquid assets to the kid that is married – into their digital wallet,” continues Raczynski. “This is a self-executing smart contract on a blockchain where, in the future state, no human (lawyer) intervention is needed.”

The importance of oracles

It should be noted that the effectiveness of the above scenario assumes the availability and accuracy of blockchain “oracles” to determine the “aliveness” of the parents and the “marital status” of the children. This could be problematic in the real world. Not all deaths may be recorded electronically in some jurisdictions. Fragmentation could be a problem. In the U.S., for example, the 50 states manage their own death registration systems.

In other words, in this scenario, as in so many others, one may have to wait for real-life blockchain oracles to “catch up” before blockchain-based legal agreements can be fully realized.

Before NFTs: Surging interest in pre-CryptoPunk collectibles

The Road to Bitcoin Adoption is Paved with Whole Numbers

Tweet

Share

Share

Andrew Singer

Opinion

Powers On… Don’t worry, Bitcoin’s adoption will not be stopped

Features

Space invaders: Launching crypto into orbit

Features

What it’s actually like to use Bitcoin in El Salvador

‘Account abstraction’ supercharges Ethereum wallets: Dummies guide

Can Bitcoin survive a Carrington Event knocking out the grid?

2023 is a make-or-break year for blockchain gaming: Play-to-own

D&D nukes NFT ban, ‘Kill-to-Earn’ zombie shooter, Illuvium: Zero hot take — Web3 Gamer